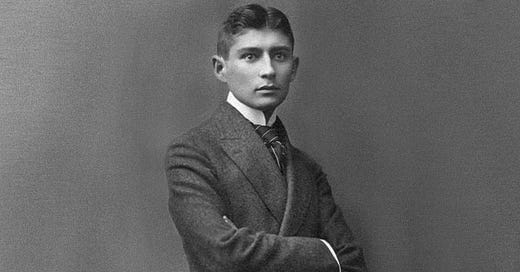

If there is any writer marked by the posthumous, it is Kafka. In his lifetime just a handful of his works were published. There were two book length collections: Meditations and A Country Doctor. A Hunger Artist was published just after Kafka’s death. In addition to that he published a handful of his short stories in his lifetime—“The Stoker”, “The Metamorphosis”, “The Judgment”, a few others. His three novels—Amerika, The Castle and The Trial—were unpublished at the time of his death in 1924, at the age of 41. Kafka’s legacy is in many ways the legacy of Max Brod’s foresight. Kafka asked for his works to be burned after his death, but Brod knew better. The Kafka we know then is the Kafka of the unpublished, of the draft and the manuscript. Kafka’s work itself is like one of his unsettling interiors, an archive that extends back towards the horizon. The further you encroach into the room, the further back the shelves extend. Perhaps a stack of forgotten notebooks, perched perilously atop correspondence of no consequence, will fall and bury you as you attempt to venture forth.

We, us critics, have been actively producing such a strange space when it comes to Kafka. We are perpetuating the archive. We have been over Kafka with a fine-tooth comb. Since Kafka’s literary works are excessively finite there’s a real risk this cottage industry might simply expire. This would be bad for business. A simple solution emerges: if he’s not making anything anymore, we will make more out of him. So it didn’t take long for us to start to reach into the space of what I will term the hypograph: letters, diaries, notebooks, drafts and manuscripts. We’ve even published his fucking office correspondence. Why this term hypograph? Ephemera is too broad a term and doesn’t capture the strange way we treat these objects as literary artefacts in and of themselves. Paraliterary and subliterary are both terms that denote common taste, as in that which is not quite proper literature. The term “personal writings” fails to convey that some of these materials are literary. They are all part of the archive certainly, but I am interested in their status when they are removed from the archive and put into commercial circulation. Hence hypograph. Graph, in its origins, refers to that which is written down. Hypo can mean low, but it also can mean under, beneath. In a real sense letters, diaries and notebooks are literally underneath the work of art. Below the surface, the fragment.

I have to admit I am a sceptic of the value of hypographs. The work must be, in some sense, accessible to us as is. If this is not so then we are forever beholden to the private. And a work of art cannot, by definition, be private, because it is facilitated somewhere between itself and its viewer. Moreover, such a view betrays a strange idea of human life: our truest self is in our personal documents. A deeply unkafkan insight. It is there, in these personal documents, that we do our best lying.

And yet we dig. Since nothing happens in the present, the past must gain a new depth. It is not just Kafka, in general we’ve become obsessed with discovering fragments, digging through archives. Literary editors and scholars see themselves not so much as architects but as archaeologists. No architect ever unleashed Tutankhamun’s curse or unveiled Pazuzu.

This weariness of mine was elevated when I read The Lost Writings, a collection of Kafka fragments published by New Directions in 2020. The publication received favourable press. The front and back matter say that these writings of Kafka’s were unearthed (like an artefact!) by Riener Stach, and two (two!) have never appeared in English before. Then, the book’s front matter goes so far as to tell us this: “All are marvels: even the most fragmentary texts are revelations.” I understand that marketing can never be prudent and measured, but even this seems a little extreme. Some of the fragments are great, and display all the hallmarks of Kafka’s writings, a sense of foreboding dropped into an ordinary interaction, a moment of confusion spun into a structure of disorientation, impenetrable mysteries and infinite corridors. Others are less compelling. For example:

It is always very early morning in this city, the sky is a level, barely broken gray, the streets are empty, pure and silent, somewhere an unfixed shutter is slowly stirring, somewhere the ends of a cloth that has been laid over the rail of a balcony on one last story are shifting, somewhere in an open window a curtain is billowing, otherwise there is nothing moving.

This is fine, I suppose. It is an imprecise passage that does not reflect the care Kafka would put into a more polished piece. The cloth is shifting? The curtain is billowing? How ordinary. If there is a revelation here it is that Kafka was, just like us, a mere person. His works did not emerge in perfect form from the tip of his pen, he did, occasionally, need to edit his work.

One of Kafka’s great influences is Flaubert. Kafka’s love of Flaubert is well documented, he raves about him in his letters to Felice. Vladimir Nabokov, in his lecture on Kafka’s Metamorphosis, notes that Kafka’s coldness stems from his love of Flaubert, from him Kafka derives an “ironic precision”. This is of course part of Kafka’s greatness; with all the stuffy rectitude of legal and scientific discourse we learn of the most horrible things. Much like Flaubert (more on him next month!), however, this is the result of careful consideration. Kafka, we know, agonised over his writings. Given this, shouldn’t we be at least a little prudent in which of his fragments we publish?

Well of course there is a pragmatic concern. So much of Kafka scholarship leans into his letters and diaries and it would be unwise to not make use of these resources. An example: allow me to grab a book at random from my small collection of texts on Kafka, Pascale Casanova’s Kafka, Angry Poet. I haven’t read this one yet, but it looks promising. I’ll open it to a random page: 290 on my left, 291 on my right (this is how books work). On my left, a page dedicated to analysing Kafka’s infamous letter to his father. On the right the analysis of the infamous letter ends, and we pivot immediately to Kafka’s diaries. Casanova leans on these sources to add evidence to the central claim of her study: Kafka was a radical social critic. The materials of course help adjudicate this claim, but political readings of Kafka are possible and evident from his texts alone, mysterious as they are.

The point of this little experiment is not to shame Casanova who strikes me as an able and worthwhile critic. Rather it is meant to be indicative of a certain state of both Kafka studies and literary analysis in general. We want the confessional materials, we want the archive, we want the hypograph. We want to close the door in a definitive manner. The great frustration of Kafka is his “ironic precision.” His novels deliver scenes but they do not deliver judgments. They build a world of such oppression, but it is such a human oppression that we do not know if we should read them as personal or social tales. His works have the power of fairy tales—I have often thought Kafka would be quite appropriate for young children—whose morals expand in an incredible number of directions. We would like to squash this and show that our reading is alone the best one.

The argument against this, I suppose, is that hypographs provide us with hitherto unattainable insights. This idea is at the heart of Saul Friedländer’s 2013 Franz Kafka: The Poet of Shame and Guilt. It is no surprise that Friedländer is a historian by training, an entire academic profession of shameless gossipers. Friedländer wants to point out that Kafka was “the poet of his own disorder.” This is to be contrasted with any reading that places him in metaphysical or religious context. This is of course a strange view of how different readings interact with each other; it is entirely plausible that text operates on both an existential level and a metaphysical one. Yet also such a reading presupposes we will get access to Kafka’s own disorder. The solution here is reversed engineered, the claim only possible because we have in fact published Kafka’s personal writings. Friedländer utilises these hypographs for underwhelming purposes. We learn that Kafka feels betrayed by his sister Ottla around the time he pens The Metamorphosis. Now we can conclude that The Metamorphosis is a tale of love and treason. Spectacular analysis.

I’ve been on the war path here, but there is one thing that gives me pause: the fact that one of the single greatest works on Kafka does in fact centre his letters. This is Elias Canetti’s Kafka’s Other Trial. Canetti centres Kafka’s letters to Felice as a way of exploring Kafka and his work, especially The Trial. Yet, if we read Canetti’s text carefully, we will notice something strange about how he proceeds.

Firstly, Canetti is extremely trepidatious about his enterprise. He begins by saying he has immense respect for those who are wary of using such personal materials to understand an author. Alas, Canetti is not one of those figures. Although, through his little book, Canetti will hem and haw against reliance on the letters. The following is characteristic of this:

If there were any need to enhance the novel’s significance, a knowledge of the letters to Felice would provide the means for doing so. Fortunately, there is no such need. In no way, however, do the following considerations, intrusive as they may be, subtract anything from the novel’s ever-increasing mystery.

If this is so then why bother reading the letters at all? In an earlier passage Canetti even goes so far as to reverse the relationship between the personal and the literary:

There are writers, admittedly only a few, who are so entirely themselves that any utterance one might presume to make about them must seem barbarous. Franz Kafka was such a writer; accordingly one must adhere as closely as possible to his own utterances, with the risk that one might seem slavish. Certainly one feels diffident as one begins to penetrate the intimacy of these letters. But the letters themselves take one’s diffidence away. For, while reading them, one realises that a story like The Metamorphosis is even more intimate than they are; and one comes at last to know what makes it different from all other stories.

It is his fiction that is personal, intimate. The paradox here is that this can only be understood from reading the letters, but this is such a particular way to proceed. Canetti’s great caution is important because it forces him to deliver an exceptionally careful analysis of the letters, one that proves his respect for those prudes who would rather look away.

Late in Kafka’s Other Trial Canetti finally argues for his enterprise: “only concrete inquiry into particular human beings makes gradual advance possible.” This is an argument for the reading of letters and personal items certainly. Yet in this passage, Canetti also makes something else clear. The letters to Felice are singularly useful, “in Kafka’s case, there is even more to it”. What is apparent in his letters to Felice is apparent in his fiction, his deep obsession with power, his attempt to “withdraw from power in whatever form it might appear”. This then is a crucial part of Canetti’s argument, above and beyond the standard deployment of hypographs to comprehend a writer. That Canetti bothers to make the argument at all is crucial. For Canetti, the letters to Felice are not beneath the literary body of Kafka’s work, they are an essential part of the literary body of work. Do they provide insight into Kafka’s soul? Well, Canetti won’t quite commit to that claim, after the letters you realise how personal the stories are. Nor will Canetti say that the letters are the key to understand Kafka’s oeuvre. What are they then? Singular literary artefacts in and of themselves. You will be hard pressed to find a scholar today who would make such claims or one who would handle these details with such care. And finally let us note that Canetti makes his argument for one part of Kafka’s personal materials alone: The Letters to Felice. Not Kafka’s letters in general, not anyone's letters whatsoever, but specifically the Letters to Felice.

As for Kafka’s fragments and drafts, great use of these has also been made. I have in mind Pierre Senges Studies of Silhouettes. Senges’ little book uses unfinished Kafka fragments as points of departure. This is all classic Senges, who leans into the absurd of literature. His other books include a story about assembling the Fragments of Lichtenberg and another about Ahab trying to sell the story of Moby-Dick. In this tongue-in-cheek fashion Senges takes the incompleteness of these Kafka fragments, many of which are no more than a sentence, and spins them into his own tales. It admits, in certain sense, that they weren’t really stories anyway. It also stakes a claim similar to Canetti’s, to make a special claim for the literary status of these hypographs. Senges’ gambit is that, in fact, the fragments aren’t really literature. At least not yet. And so his book asks what literature can be made from these fragments. The result is not a work by Kafka but by Pierre Senges.

It would be useless to say that the letters are useless. That an author, especially one as important as Kafka, should not have an archive which scholars can peruse. Kafka, however, is simply a symbol of a wider problem. And Kafka should be attacked first because he is the figure in which we can justify these excesses. After the well has run dry, after we have begun to publish poor fragments and office documents, should we not ask if some restraint is called for? Not everything is useful. If these objects exist to be bought, sold and to fake the experience of revelation then they should be resisted. Canetti has the unique pleasure to be somewhat early to this party. Senges turns these fragments into something else, something his own. Is that Kafka? No. Must we damn Kafka to an eternity of posthumous publication? What is next? The report cards of Franz Kafka? The tax returns of Franz Kafka? The visa applications of Franz Kafka? And god forbid this expands to other writers. I do not want to be subject to the complete emails of J.M. Coetzee or, even worse, the collected DMs of Sally Rooney. The shame of it will outlive us all.

Duncan Stuart is an Australian writer. His writings have appeared in Firmament, 3:AM Magazine, The Cleveland Review of Books, Jacobin, and Overland. He publishes a monthly substack, Exit Only, and can be found on Twitter @DuncanAStuart.

I enjoyed reading this immensely—the critique of the entire Kafka cottage industry (all the minor writings and fragments and unexceptional memos!)—and the reflection at the end on how to write about our literary heroes in a more novel way. I’m so intrigued by the Elias Canetti book mentioned here…will try to find a copy soon!