I never understood why almost all Westerns are shot in desert landscapes! – Anthony Mann

Anthony Mann’s string of Westerns in the 1950s represents a seismic shift in the genre. As the above quote alluded to, the most discernible shift is a radical change in landscapes, from the famous Monument Valley and vast desert expanses of John Ford films to a more rounded environment involving a range of vegetation and climates. However, Mann knows that it isn’t as simple as pasting a typical Western template onto his new, pretty wallpaper. For starters, the visual hallmark of Western genres, the wide shots, is at odds with the new landscapes. The infinite vastness of the desert, together with its forbidding mountains and hellish valleys, provide the ideal battleground for its outsized heroes as they forge new myths in the face of unforgiving aridity. In contrast, the lush verdure and beautiful plenitude of Mann’s landscapes point not to a destiny being manifested, but a paradise found—a flourishing civilization that’s constantly at war with the lofty lies tacked on by its deluded denizens. How can the heroes exert their machismo in a landscape that’s so welcoming?

Mann’s characters themselves appear to realize this as they simultaneously move towards and away from the mythic impulse. The landscape is not conducive to their kind of macho mythicizing, but they are still drawn to its tantalizing allures. Inevitably, this change in landscape transforms the emotional, social, and political landscapes, with psychological scars and vulnerabilities inadvertently coming to the fore even as characters try to overcompensate by channeling the swaggering exuberance of Westerns. The heroes are, thus, those who are more cognizant of this dissonance, gradually allowing their bravura to give way to a world-weary lugubriousness, though the occasional frisson for an unattainable nostalgia seizes their entire being. They recognize the brash foolishness of their fellow travelers who headily plunge into the paradoxes of this myth though they can’t help but envy them. A portrayal of their dialectical struggle, in Mann’s hands, ultimately becomes a meditation on violence.

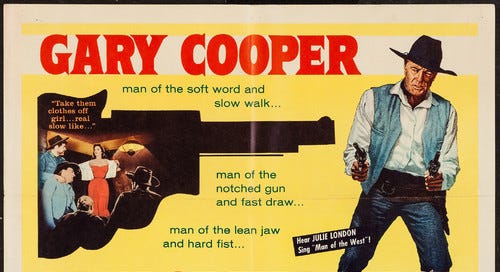

All these themes are crystallized in Man of the West (1958), his final film in CinemaScope and, in a way, a fitting swansong for the themes explored in his previous Scope Westerns. The hero, Link (Gary Cooper)—a literal and metaphorical “link” between the two worlds—travels on a train to find a teacher for his small community, and meets a garrulous salesman, Sam (Arthur ‘O Connell) and a saloon singer, Billie (Julie London), during his travels. An attack by bandits separates these three people from their train, and, to find shelter, Link leads his companions to a seemingly abandoned shack located at the edge of the valley. The shack is revealed to be the hideout of the bandits, with their leader Dock Tobin (Lee J. Cobb) being Link’s uncle. The trio’s only chance of survival is for Link to rejoin his old fold and rob a bank with Dock and his cohorts.

Link’s regression to his past life is marked by a progression in landscapes from “the vegetal to the mineral world” (as both Sarris and Godard have aptly remarked). In reality a regression, it is also a cinephilic regression, as the verdure gives way to the desert of older Westerns, a desperate sojourn in search of a fitting myth. A return to an outmoded past, however, brings only an inversion of its expected emotions—the triumph of Westerns gives way to tragedy. No longer are the mountains and valleys hallmarks of heroism, but witnesses to a spectacularly futile fall.

Crucial to this journey is how machismo operates within the fabric of society and how violence is encoded into the DNA of Westerns. A seemingly simple shift in landscape lends itself to different modes of filmmaking, broadening the scope of Westerns. In a film like Man of the West, where the landscape keeps changing, multiple modes come into conflict with echoes of the old West, finding its terrifying grip in one scene while floundering hysterically in another. The shack itself is perched felicitously at the boundary of the vegetal and mineral, containing both the death of the desert in the form of its dead trees and animal skulls, and the verdure of the forest through its green grass. Finding scant success in their attempts at robbery, the only option for Dock is to turn towards a more successful past heralded by the arrival of Link.

Dock is still a menacing figure in these parts, with his name still mentioned with fear and fascination among the train travelers. However, his menace is far more powerful when restricted to the interiors where myth takes free reign, shutting off the external reality from entering its realm. Link’s return to his shack is accompanied by deep-focus shots, developing a harrowing psychodrama between Link, Dock, and the latest hot-headed “nephew”, Coaley Tobin (Jack Lord). Machismo’s disposition to dominate the feminine is at its ugliest display here, with Coaley demanding Billie to strip as he holds a knife to Link’s throat. The stripping is alternated with deep-focus shots of the trio, as we helplessly watch Link’s powerlessness interact with Coaley’s arrogance and Dock’s commanding silence. Dock does eventually bring the proceedings to a close, only after reminding Link of his power.

Outside, however, Dock’s stentorian swagger seem like the raves of a megalomaniac. Mann infuses his film with the spirit of Greek and Shakespearean tragedy; the settings themselves evoke a theatricality in his CinemaScope framings. Critic Robin Wood, in an essay on Mann’s Westerns, likens Dock to a Lear-like figure, with daughters being replaced by “sons”. Despite the depths of his cruelty, Mann renders him more like a pathetic figure woefully flip-flopping in a time period that’s quickly slipping from his grasp. His delusions of grandeur are terrifying in close-up, but anachronistic in long shot. The casting emphasizes this sharp contrast, with Lee J. Cobb’s explosive theatricality at odds with Gary Cooper’s magisterial cinematic presence. These dialectical contrasts reveal deeper complexities in the Western genre beyond its fundamental trappings, with space mediating its modes of expression.

All the modes, however, pivot around the notion of masculine violence, and this is true even when the hero distances himself from it. Link’s self-awareness might differentiate him from Dock’s maniacal delusions, but he is never fully comfortable with the humdrum banalities of the modern world, as illustrated by his discomfort on the train ride. Sam remarks that we eventually get used to everything, though Mann is a lot less sure of that. The tugs of a glamorous past still have their irresistible pull, and this dialectical discomfort comes to the fore in a quasi-revenge scene. Dock goads Link into a tussle with Coaley, and Link plays on, engaging in a fistfight that constitutes one of the most disturbing scenes in the film.

The Link of the past re-emerges, not only in his fighting prowess but also in his desire to exact revenge on Coaley for his and Billie’s humiliation. Link counters Coaley’s machismo with a frightening machismo of his own, stripping him of his clothes until the act eventually becomes too barbaric for Link himself. As Dock’s deluded enthusiasm reaches a feverish pitch in this sequence, Link convulses in horror. Dock has successfully wrung out the repressed Link—a peaceful existence is impossible if violence is not completely abandoned.

This pushes the Western itself into crisis, as resuscitating the touchstones of the genre only ends up bringing its convictions and violence to the fore; a pastiche at best. Dock’s desperate attempts to summon the specters of a fabled past only lead him and his crew to a ghost town that’s inhabited by a Mexican couple. His glamorous dreams of robbing a legendarily guarded bank are rendered limp in an instant, and his henchman’s callous shooting of the Mexican woman appears all the more deplorable.

The famous desert has lost all its promise, and all that’s left is for Link to exact his revenge. In his essay on Man of the West, Godard pointed to the lateral tracking shot showing the vast stretch of the abandoned town accompanying Link’s slow movements towards the dead henchman. While this accentuates Link’s own discomfort at such a landscape, Mann’s asymmetric framing also points to an unfolding of Link’s slightly dislocated temporality as compared to that of reality. Tremors of modernism are felt in the cracks of classicism, or is it the reverse?

While the violent myths of the West result in a muddled masculinity, it also fractures Ford’s cherished themes of family and community. Mann’s females seldom take center stage, but their lingering presence only further complicates the idea of the “Man of the West.” Even in the “placid” life of cities, Billie is never respected and is leered at. Like Janet Leigh’s Lina in The Naked Spur (1953), she falls in love with the hero only because he does the bare minimum of seeing her as a human being. As Link is already married, no happy ending is possible, but even if it weren’t the case, Mann makes it clear that Link’s violence is never going to let him go. Mann’s sustained portrayals of his males allow him to explore troubled masculinity far more than his wounded females, but he still leaves these kernels of dissatisfaction for future directors to explore.

If Westerns are seen as an immutable genre whose biggest developments are brought about by John Ford and later “revitalized” by Leone and Eastwood, it probably points to a particular (though prevalent) brand of cinephilia that views cinema and genre through designated signposts which fail to understand a genre as one possessing its own cinematic language. This is understandable, given the influence of marketing and its schematic reductions of films to a few big names. However, the Western, like other genres, also possesses its own digressions and detours, incursions and inversions, and riffs and reversals when handled by filmmakers who are able to bring their voices to a seemingly restrictive category. Mann’s Man of the West signifies an end of the Western in the Godardian sense of the term, paving the way for a modernist approach to the Western pioneered by Monte Hellman. Through its dialectic of interior and exterior, architecture and landscape, theatre and cinema, Man of the West situates itself right at the boundary of classicism and modernism, thereby showing that any recourse to the Western can only be possible by grappling with its myths or from a profound sense of loss.

Anand Sudha is currently doing his PhD in Applied Physics while trying to squeeze film criticism in his spare time. He has been published in outlets like InReview, Film Companion, and Ultra Dogme among others.