Sweet Smell of Success (1957) opens with Sidney Falco, played by Tony Curtis, in a bind: he’s a press agent, and his talent is calling him, asking him why he hasn’t been able to get their names into the totemic JJ Hunsecker’s column. The answer is more incestuous than you might expect: Hunsecker has asked Falco to break up his sister Susie’s romance with a guitar player, Steve, and he hasn’t been able to do it. The viewer might assume because they’re watching a Hollywood movie that Steve is a lowlife, but the movie’s first surprise is that Steve is quite stolid: dignified and honorable to the point of being annoying. He has integrity, “acute, like indigestion,” as Falco later puts it.

It is at best a strange thing for a man as powerful as Hunsecker to ask of someone else to do. He could end the relationship with a mention in his column or even with an accusation. Hunsecker, to paraphrase Falco, has told presidents what to do and where to go. So why does he need someone to break up his sister’s romance on the sly?

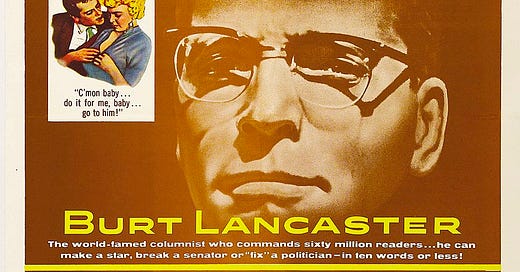

JJ Hunsecker, played by Burt Lancaster, is based on a real-life columnist, Walter Winchell, whom the audience of the 1950s would have known for his rabid opposition to fascism and equally rabid support of the House Un-American Activities Committee, and also for siccing the FBI on his daughter’s would-be husband and eventually chasing him all the way to Israel, all for the crime of wanting to marry her. Hunsecker, as his stand-in in this roman a clef, is as monomaniacal in his self-righteousness as he is in his entitlement, and what preoccupies him above all is a desire to keep his relationship with his sister “at par.” Meaning she’s not to grow up. Meaning no boys, and certainly no men. He emphasizes, in justifying himself to Falco, that Susie is all he’s got.

The menace of incest and sexual assault hangs over the movie although none of the characters ever explicitly discuss it—which is no surprise, as it’s a Hays Code movie—but that, ironically, adds to the menace: whereas a contemporary piece of Hollywood film would fill us in on all of the lurid details, the reality is that your average person avoids discussing the plague of sexual assault and incest in this country unless the people involved are famous enough to end up in tabloid headlines. You’re far more likely to be preyed upon by someone you know than by a stranger—Sweet Smell gets that right, too. Perpetrators have an obvious reason enough to keep their actions to themselves, and victims tend to stay quiet for a myriad of reasons ranging from shame to fear of retaliation. Thus the negative space is also the subject of the movie: it would be easy to assume that what happened between Susie and JJ Hunsecker is so taboo that it’s never even discussed. The mere intimation of Hunsecker’s menace to Susie is like a shark fin appearing in the water. For context and a source of extremity, we are forced to rely on how the two behave, and Susie’s terror in Hunsecker’s presence would appear to be not of someone who’s merely afraid of being controlled by her brother. She’s more often than not on the verge of a panic attack, shaking visibly, averting her eyes, her voice wavering when she’s not stuttering. And yet, we do not know in any concrete sense what happened between them. She verbalizes fear on Steve’s behalf, and indeed for his life, but never her own.

Sweet Smell bombed at the box office. It takes Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis, two Hollywood heartthrobs, and makes them into vicious, conniving perverts (which Burt Lancaster, at his worst, was in real life), and they play them with relish. The role was Curtis’ first real opportunity to make himself into a serious actor, and he practically dances through the movie, delighting in his character’s manipulations and drooping visibly with his failures. His manner is always giving away the lies his mouth is telling—he “reads as he runs,” as Steve points out—and Susie, Hunsecker, and Steve, along with what seems like a dozen other minor characters, see through “the boy with the ice cream face” over and over again. When he tells a lie and gets away with it on his own, it’s a shock, and the rest of the time, it’s only Hunsecker’s backing that keeps him from getting a dusting from the men in the movie who have anything more than his scoliotic moral backbone.

While Hunsecker and Falco do seem to enjoy their machinations, at times, elsewhere they explain their behavior in terms of their “nature.” They know how they come across. They haven’t a “drop of respect… for anything alive,” as JJ’s secretary puts it, and they do live in “moral twilight,” but there is also a pathetic loneliness about them that reeks of self-absorption.

But what Curtis and Lancaster convey most powerfully is that their character’s turpitude is only surpassed by their denial of it. Both JJ and Sidney’s need to manipulate the moment in service of their own greed is their only function that calls upon their cold, calculating empathy. By treating other people as means rather than ends, JJ and Sidney hope to milk what they can out of their marks before they’re finally exposed for what they really are and are left entirely on their own. JJ says his sister is all he’s got, but he means “got” quite literally, as it turns out: he treats his sister just as instrumentally as he does everyone else; he only pretends to love her.

Falco’s secretary, Mary, setting us up quite blithely in the first ten minutes of the movie, asks Falco why he stands for the treatment he gets from Hunsecker.

Well, Hunsecker is Falco’s “golden ladder” to a place “that’s always balmy.” “In short,” Falco tells Mary, “from now on, the best is good enough for me.” The floor, in other words, will be his ceiling. And if he’s got to ruin his boss's sister’s life to do it, he will.

Inevitably these men are bad tippers: as Sidney leaves his office and heads into the blisteringly cold night, Mary reminds him to take his topcoat, and Falco retorts “and leave a tip in every coat check room in town?”

Hunsecker and Falco’s plot hinges on keeping Susie and Steve from knowing Hunsecker is the puppeteer; nonetheless, Susie seems to be onto him from the jump. Many have said that Susan Harrison’s performance is the weakest part of the film, but she plays Susie’s diffidence and fear with stuttering grace. Susie’s fear and indecision in the first half of the movie could be mistaken for diffidence, but it’s as much a sign of her intelligence: she knows what kind of man her brother is and must move carefully and make sure Steve does as well. To thrash about and make a lot of noise about her brother’s depravity risks retaliation for both of them, and Hunsecker, as we see, has the cops, the politicians, and the press ready and willing to help him, because of course Hunsecker has a mountain of dirt on all of them.

Leaving a bar with Falco in a taxi, Susie says she’d like to see into Falco’s “clever little mind” to see what he really thinks of her brother, and Falco puts on the opprobrium like a garish hat, asking her where she comes off making a remark like that. (He’ll later take the same tack when Susie accuses him of plotting with her brother to put her boyfriend in the hospital, and she won’t believe him then, either.) The point of his anger, after all, is not to prove that he is telling the truth, but to show that he is ready to defend his honor, and that means his anger is a threat.

Susie’s not impressed: it’s telling in this scene how little time Susie spends even looking at Falco, never mind interpreting his gestures; meanwhile, Falco watches her every move and externalizes every emotion he has. In fact he goes through the movie pacing, biting his fingernails, and wearing his astonishment like a dishrag. Susie knows what kind of man she’s with: she doesn’t need to watch him. But Falco doesn’t know where Susie stands.

Susie asks him, “Who could love a man who makes you jump through burning hoops like a trained poodle?”smirking again, and handling the final appellation like it was a fine piece of jewelry she was putting on for the night. Falco sits back very slowly, barely listening to her, trying to countenance that a woman he’s used to patronizing has pointed out just how pathetic and servile he really is. And then she delivers the kicker: she intends to marry Steve, and on top of that, Steve is the first man she’s ever really loved. She delivers the line like it’s a threat, which of course we find out to Hunsecker, it is.

The subtext of the conversation is that Susie does seem to know Hunsecker is evil. Which means his plot to break up their romance is kaput from the start. Which in turn means that as conniving and evil as he is, he’s also naive.

The movie unfurls with one depraved attempt at manipulation after another. Falco turns over his friend, a cigarette girl named Rita, who lost her job because of the one columnist’s advances, to another columnist, who will in turn print an item accusing Steve of smoking marijuana and being a communist. Rita, who seems to really be fond of Falco, only acquiesces in the face of Falco’s depraved indifference when he reminds her that the second columnist can get her back the job the first columnist got her fired for. And of course, what she was fired for was rejecting the first columnist’s advance at eleven o’clock in the morning.

The manner in which Rita's is traded blithely for a hitjob reminds us these are men who have spent so much of their life manipulating others that they end up surrounded by factotums and people looking to use them. They briefly enjoy the skill with which they manipulate others, but sooner or later they have to sift through the wreckage they create.

What’s so disturbing is that Hunsecker believes his own demagoguery. It’s easy to forget, with all of the moralizing drivel that Hollywood tries to jam down our gullets, that evil more often than not justifies itself, believes itself good or at least worthy of all of the power and riches it lays claim to. It would somehow be mildly reassuring if he were just a conman, but the glint in Lancaster’s eyes reminds us that the true believers are the real threats. This is a man classically trained in the ends justifying the means. He has the talent for circular logic and self-justification of an apex narcissist. Why is Steve immoral? Because he’s insulted Hunsecker, who represents the greatest country in the world and its people, who are moral, because Hunsecker represents them. It’s the sort of logic that permits anything, justifies anything. It’s the sort of logic you can build an empire on.

The film, which its director, Alexander Mackendrick, dismissed as a melodrama, takes its most operatic turn near the end when, in response to Steve being busted for marijuana possession (planted by Falco, of course) then severely beaten by Lieutenant Kello, Susie announces to Falco that she is going to kill herself and that he’ll be the one who has to take the blame. What elevates the film above melodrama is that Falco’s response is to laugh. The look Susie wears in response is not further rage but abject despair.

It’s worth imagining what Susie might have hoped for out of the gesture. She has been betrayed at every turn, lied to and manipulated, on top of whatever unknown things Hunsecker has done to her in the past. Falco has pretended to be a friend to her, and she knows he has played a part in Steve’s assault. The only thing she is guilty of is falling in love with someone who is so dreadfully earnest that he can’t help provoking the 1950s equivalent of Tucker Carlson. Nonetheless, she might have hoped that, seeing her in such a state, Falco might have repented and or at least admitted wrongdoing.

But just as Falco seems incapable of noticing Susie’s fear of her own brother, so here the authenticity of her abjection seems to sail over his finely coiffed hair. He turns into an engine of contempt. He launches into a misogynistic rant: she needs to stop “thinking with her hips” and walking around on her “bird legs,” then backtracking, he says he can’t blame her, it’s women’s “nature to think with their hips” (he seems incapable in the course of this short rant of not thinking of Susie’s legs); all the while Susie’s face has the blank look of shock and dissociation. Falco walks around her, pouring himself a drink, talking to everything but her face, almost as if he’s stalking his prey. Blithely unaware of Susie’s dissociative state, he rambles until she runs into her room and locks the door.

Falco, like many people in the face of a genuine suicidal threat, regards her threat as a bluff, or a test, a manipulation: a way of getting him to admit his involvement in Steve’s arrest or turning over her brother. After all, there’s no way, at this juncture, that Susie can believe Falco wasn’t involved. But where men like Hunsecker and Falco operate with a desire to will reality, they fail to see that other people, including those they claim to care about most, have their own desires, their own agency. Falco can’t see that his actions might drive someone to suicidality because his entire being is contorted justifying those actions.

So Falco’s perverse joke, whispered through Susie’s door, “that body of yours deserves a better fate than tumbling off some terrace”—as if he’s forgotten whose terrace it would be—is where he shows Susie nearly fatally who he is. Falco’s imagination is such that he seems to believe her next move after threatening suicide will be to offer herself up to Falco to save Steve. When Susie doesn’t come out of her door in her negligee, he finally seems to grasp that Susie is not seducing him to save her boyfriend.

And of course, Susie does try to kill herself. Falco seems utterly flabbergasted by the attempt, only narrowing saving her from the aforementioned tumble. His apology is circumlocutions, but for once, his tone suggests honest confusion: he apologizes if he “did anything or said anything”—as if his entire dehumanizing rant, his direct involvement in Steve’s beating, his aiding JJ’s goal to keep Susie “limp and dependent,” were not the source of her suicidality in the first place.

Just as Susie was watchful and contemplative in the taxi with Falco at the beginning of the film, she looks on post-attempt with clarity as Hunsecker arrives, not only finally and totally comprehending her brother’s depravity and contempt for her intelligence and autonomy but allowing him to act on it in a way that shows him for who he really is. What Susie has is not an epiphany of the intellect but of the will. While Hunsecker beats Falco, accuses him of trying to assault his sister, Susie stands by. She doesn’t have to say anything because she knows the truth.

Hunsecker has no capacity for love or even friendship with another human being— that’s clear from he’s treated her and Falco—and what’s left to him are the tools of the right-wing propagandist: lying, manipulation, cruelty. These tools dull with use; eventually everyone around a person like Hunsecker sees them for who they really are, and once their power wanes, suddenly their world appears to be just as petty, lonely, and ridiculous as it really is. Hunsecker might try to destroy Steve or Falco, but what he was most afraid of has come to pass: that Susie might exercise her own free will. The last shot we see of her, she is walking out over Broadway by herself, presumably off to see Steve in the hospital. From the beginning it was clear Susie had Hunsecker and Falco pegged for conniving poltroons who only cared about themselves—that was never in question. What was in question was if she would find the courage to disentangle herself from their increasingly manic and spindly webs.

It’s common enough to think that power corrupts, but the reality is that more often it’s acquired by those who enjoy corruption. Since Sweet Smell of Success was made, the monster of demagoguery and consent manufacturing has only grown more eyes, more tentacles, and become more voracious. The only thing that might save us from its contempt and cruelty is that very same contempt, as Falco himself puts it, does occasionally make it stupid.

Evan Grillon is a writer who lives in New York City. His writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Dirt, and Triangle House Review, among others.