On December 6, 2023, I logged into X (let’s call it Twitter) to see a thread indicating some new drama in the writing world. “watching everyone celebrate what amounts to literary revenge porn against a mentally unwell woman who took her own life has me sick to my stomach,” the author Sarah Rose Etter begins. “oh you need to gobble up the suicide note? and the sexts? ok just head to Perez Hilton!”

I clicked around in a frenzy, trying to find the text at the center of the firestorm. I was shocked to learn that it was Blake Butler’s Molly, recently released through Archway Editions.

The title Molly refers to the poet and memoirist Molly Brodak, Butler’s first wife. After nearly three years of marriage with Butler, Brodak took her own life. Butler’s memoir unpacks his response to this tragedy—including his feelings about her infidelity, which he discovered after her death. This constitutes the controversy surrounding the book.

It feels wrong, in a way, to refer to the Molly controversy as such—“controversy” being the kind of word that shysters use to generate web traffic. Yet the designation seems appropriate, given that Molly quite literally has become tabloid fodder in a way that most authors could never fathom. After its publication, Molly was covered by a number of media outlets fishing for the most salacious angle on the book, the Daily Mail and the New York Post included. Both papers shouted about Brodak’s affairs in their headline. Butler would later reveal that even the Telegraph, which ran a nuanced, five-star review of the book, refused to run an excerpt unless it contained adultery.

When I finally sat down with Molly—and read Butler’s remarks on the matter—it seemed clear to me that Butler had never intended to milk the tragedy for notoriety. Yet at this point the specifics of Butler and Brodak’s situation are far from the most important conversation engendered by the book. Not only has Molly sparked discourse about the mechanics of memoir, the state of literary criticism, and misconceptions about mental health—it has challenged readers to believe in a love that resists easy interpretation.

In order to discuss the Molly drama, it’s first necessary to see if the Molly that Butler wrote and the Molly that its detractors are talking about are the same text. Upon examination, they don’t seem so similar.

Etter seems to take the greatest issue with the fact that Butler discloses Brodak’s infidelity—and, apparently, discusses it in a spiteful and vulgar manner. Primed by her assessment I approached the memoir with a critical eye, wondering if Blake’s descriptions of Brodak’s affairs would reduce Molly to an outdated archetype or linger on salacious details.

100 pages passed. The topic hadn’t even been broached yet. 200. Still nothing.

It isn’t until page 242—two thirds of the way through the book—that Butler mentions Brodak’s cheating. Etter mentions sexts, but the scene in which Butler discovers the explicit materials on Brodak’s phone only takes up two pages. Of those two pages, only four sentences describe the photographs and videos Butler finds—and Butler’s description serves primarily to characterize the content as unusual for Brodak, at least the Brodak he had known. Throughout the book, Butler quotes from Brodak liberally; this is the rare scene in which he chooses not to do so. We actually don’t see the sexts firsthand—but Molly is brimming with photographs that show Brodak laughing, smiling, cuddling with her pet chickens.

Regarding Brodak’s infidelity, Etter writes in her thread, “All of us have done things we aren’t proud of—sent nudes, had torrid affairs, slept with people we shouldn’t have.” Here, she’s trying to frame the transgression as ordinary, a hurdle that plenty of couples are challenged to overcome—but its out-of-the-ordinariness is what makes it a subject of discussion in the first place. By this, I refer not to the magnitude of the offense but to the circumstances surrounding it. Consider these two truths:

A) Molly groomed the college students she taught in addition to initiating explicit conversations on the Internet.

B) Molly was dealing with intense mental health struggles (she suspected bipolar; Butler suspects borderline), which she only began addressing through therapy during her final year of life. (Etter herself notes this, referring to Brodak as “mentally unwell”—seemingly not realizing that by sweeping Brodak in with “all of us,” she might be trivializing Brodak’s condition.)

Considered on its own, Point A paints Brodak as calculating, even vile. Considered on its own, Point B presents her as a more sympathetic character. The wonder of Butler’s book is that it recognizes that Brodak is not a “character” at all, but a real woman who deserves to be recognized in all her complexity. Point A doesn’t render Brodak a monster unworthy of love and care, and Point B doesn’t negate the pain that her actions caused Butler and others. Butler’s affirmation of this reality is not just implied in Molly—it’s the story’s central thesis. He’s careful not to render Brodak one-dimensionally, even when he acknowledges that some of Brodak’s treatment towards him might constitute “abuse.” “Do I seem like a fool, an ass? That’s fine,” he writes. “I got to share a life up close with one of the most brilliant and singularly stunning people I’ve ever met, good times and bad… I don’t regret it, never will, no matter how much pain it’s caused me, all the mental damage. I refuse, when at my clearest, to simply demonize Molly for her struggle.”

The indictment of Molly as “revenge porn” is based on the premise that disclosing Brodak’s infidelity would make her amount to less in the face of a harshly judgmental society—and indeed, the court of public opinion does not look kindly upon those who cheat. In Molly, however, Butler tirelessly argues against black-and-white thinking, emphasizing that Brodak’s infidelity does not define her nor does it define their relationship.

Would you cheat on your partner? Would you forgive a cheating partner? Would you support a mentally unwell partner? Although the discourse and Butler’s memoir stir these questions in the subconscious, Molly isn’t prescriptivist; for all the implications of morality, Butler never suggests that his way of handling the relationship was “correct”. Yet his musings ultimately manifest in a message: To love is to resist obvious paradigms. Butler didn’t love Brodak because she was perfect. Rather, he embraced her in light of her imperfections. By its very existence, Molly encourages readers to love in the same way.

Questions have been raised about the ethics of Butler writing about Brodak’s infidelity when it is known that he cheated on her as well. Indeed, it would seem skeevy if Molly discussed Brodak’s infidelity while skipping over Butler’s own—but it doesn’t. Butler comes clean about his behavior early in the book, telling the story of his courtship with Brodak chronologically. As Butler recounts it, after a massive fight between the two, he turned to alcohol and “began meeting up with other women I’d been seeing before Molly came to town… I didn’t always tell her what was going on, instead lying by omission.” He started sleeping with another woman, only stopping after he ran into her at a reading “with Molly on [his] arm.” Butler divulges his troubled internal monologue—“How long could I go on acting out against the idea of who I claimed to be and still be me?”—and ultimately admits guilt—“I’m not proud of having lied to her, broken her trust.”

So is that case closed? Is memoir writing a tit-for-tat, sin-for-sin exercise? I doubt anyone truly believes so. The questions posed go beyond the issue of cheating and more broadly touch on whether it’s ethical to publish a personal account if it includes information that might portray someone in a less than flattering light.

Butler asserts that Brodak would have defended his choice to share his memoir: “I have the right to tell my story. I learned that from Molly,” he posted on Twitter. To someone who hasn’t read the book—or isn’t familiar with Butler and Brodak beyond tabloid hype—the claim might seem tenuous. But the proof is in Brodak’s own work: she herself was a memoirist who preferred the no-holds barred approach, and this is well documented in Molly.

Brodak is perhaps best known for Bandit, which unpacks her relationship with her family—most notably her father, a serial bank robber. According to an interview with NPR, both her sister and her mother warned her not to write about him. She persisted anyway: “I was so beyond that point when I started writing it,” she said. “I was so ready to do it, and I was so ready for all of the light to shine on the story.” Her obituary in the New York Times called the work “unsparing,” complimentarily.

The irony should be obvious enough already, but Molly makes it more so: in one passage Butler discloses that Brodak had started working on a draft of a memoir about him, titled My Novelist.

Would you write about your partner? Would you enter a relationship with a partner who would write about you? You shouldn’t have to, and no one is begging you to. But evidently, as does Butler, Brodak saw the practice of memoir as a lens through which to see the world more clearly—in all of its terror and beauty.

Another point of contention in the discussion of Molly is not whether Butler should write about Brodak negatively, but whether Butler should write about Brodak at all in her absence. This debate, at least on the part of some readers, is grounded in matters of identity—is there some injustice in letting a man tell a dead woman’s story? Bookforum remarked that the shadow of Ted Hughes’ relationship with Sylvia Plath hung over the book, if only due to circumstance. The concern that Butler might be getting the “last word” regarding Brodak’s story—that the ups and downs of her personal life might overshadow the power of her poetry—is understandable. In fact, within Molly’s pages, Butler himself seems disturbed by this possibility.

Again, it’s worth considering that Butler quotes generously from Brodak’s works throughout the memoir, reminding the reader that she was a gifted wordsmith and could explain her own emotions and eccentricities far better than Butler ever could. Near the end of the book, he looks toward the precedent Brodak set as a memoirist in order to assess how he might depict her perspective most effectively. After explaining that Brodak concluded Bandit with a letter from her father—“It’s the least I can do now, to let him speak for himself,” she writes—Butler ruminates on how to best allow Brodak’s voice to be heard.

A particularly sympathetic reader—or one wanting to play devil’s advocate to the critics—might argue that Butler publishing Brodak’s suicide note is a way of letting her speak for herself. (Might summarizing her words have caused a greater stir, had Butler chosen to go that route?) Butler himself doesn’t believe this is enough: “In earlier versions of this manuscript I’d imagined sharing Molly’s suicide note could do the same, though as more time passed and the story shifted, I realized the letter wasn’t really it… I realized there was still more that she could say, in the only way she’d ever found to speak her truth—through poetry, the very thing that’d saved her life time and again.” He goes on to share Brodak’s final poem: “Camp,” which, as a CNN op-ed notes, references both the concentration camps in which her ancestors were killed and the children’s summertime ritual.

Are these the perfect words? Do the perfect words exist? No, but that doesn’t stop Butler from making sincere efforts to land on them, again and again. Closer to the end of the book, he opts for a simpler, more direct approach: “I’m so sorry, Molly. I really tried,” he writes. (Note: while trying to find this passage, I learned that the phrase “I tried” appears 38 times in the book.) “I know you tried too, as best as you could. I love you forever.”

The question of Molly is especially fascinating in light of the recent autofiction boom. Autofiction—blending memoir-style accounts with fabricated details—has been around for years, if not by name then in practice. The term has been applied to everything from the works of James Joyce to Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle series to Chris Kraus’ cult classic I Love Dick—but recently it’s been most strongly associated with the alt-lit movement, with publishers such as Tyrant Books and now Archway Editions (mastermind behind a genre anthology as well as a reading series, both titled NDA) paving the way.

At many literary readings in New York and Los Angeles, autofiction has become the unspoken rule. I’ve dabbled in the art, too, and through my experiments I’ve come to understand why it’s so appealing. Autofiction allows the writer to shrug off the shame (and consequences?) that might follow a retelling of a real-life event by changing names and tweaking details, thereby creating emotional distance between the writer-narrator and the subject. It also plays into the (writerly, but also universal) tendency to narrativize our lives and imagine better ones—it can be so tempting to cast ne’er-do-well-ers as bonafide villains, to pencil in happier endings where we feel we deserved them, and so on.

I say this not to balk at autofiction (again, I’m a proud member of the club), but to underline the basic human mechanisms at play when we sit down to write our own stories. It’s instinctive to oversimplify, to dramatize, to step away from. By looking Brodak’s ghost in the eye, Butler has overridden these mechanisms—and in the process, created a work that is truly brave.

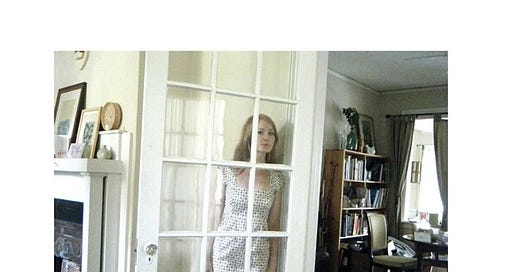

To best understand Molly, just look at the cover. The title—a simple remembrance, unfettered by description. The image of Brodak peering through the glass of a door—indicating a beauty that becomes intensified by its unknowability, and vice versa. The only thing pornographic here is the clickbait the book has been reduced to.

I'm reading this book right now and this resonated with me, thank you for putting it so clearly

People love to judge. The self-righteous 'moral' arbiter rallies a cancellation by social media pile-on. Morals are an excuse to persecute.