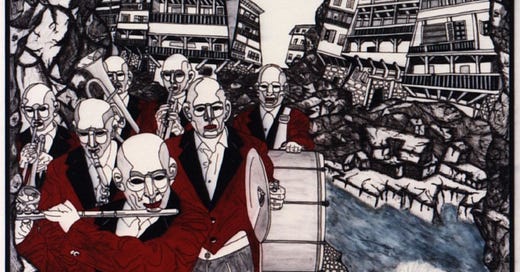

Litan (directed by Jean-Pierre Mocky, 1982)

Of the many things I wish films utilized more regularly, like untrained animals and setting appropriate architecture, is the weather. A big part of why I was so taken with Jean-Pierre Mocky’s 1982 film Litan is his choice to ground the film on a foggy fall day. Beginning with a nightmare, which may have eeked out into reality, Nora (Marie-José Nat) awakens and knows she has to find her husband Jock (Jean-Pierre Mocky) (I was certain this was a mistake in the fanmade subtitles and it should be Jacques, but that isn’t the case). They’re visiting the small French village of Litan, and today happens to be the village’s Day of the Dead festival. Nora’s nightmare included a vision of her husband dying, but quickly she realizes that the dream was a premonition.

As Nora travels through this strange village, she is accosted by people in masks as she passes through their strange ceremonies. Her geologist husband is incredulous, but as they discover that the local hospital is experimenting with the recent dead to communicate with them, that bodies are becoming glowing light worms, and the police have absolutely no intention of doing anything about anything, he begins to believe her. But there is something wrong here, and as more and more people are killed it is clear that this isn’t simply rural idiosyncrasies.

Like Jean Rollin’s Grapes of Wrath, or the opening section of George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, there are no moments of reprieve, and the film works as a non-stop fever dream. It’s The Wicker Man by way of film fantastique, but despite these comparisons it is like nothing else. You feel a bit like the protagonists when watching it, trapped in a nightmare whose propulsive pacing and striking imagery does not give you a moment to think.

Madeleine Wall is a critic and programmer from Toronto.

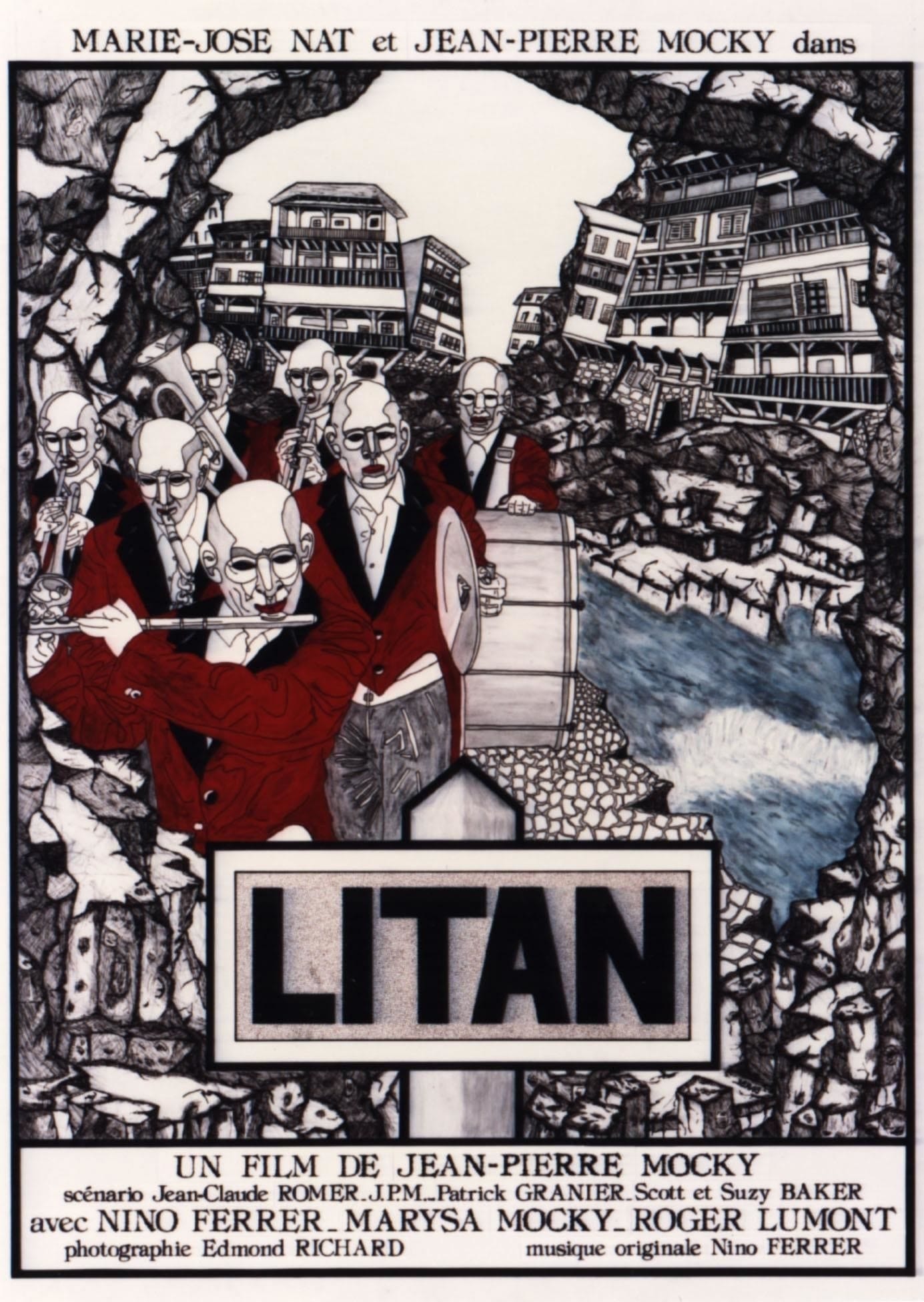

Love in the New Millennium by Can Xue, translated by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen (Yale University Press)

Can Xue – the pseudonym of a former tailor, Deng Xiaohua – renders her experimental romance as a series of dreams. Indeed, characters are caught dreaming all the time in the narrative, which follows a series of interconnected lovers and affairs, doomed and otherwise. The action is decidedly associative. Scenes dissolve in and out of each other with little of what might be called “motivation.” The peculiar quality of Can Xue’s work stems from her even more peculiar method of composition: she claims that her books and stories are records of her “performance” at the desk each day where she writes the works from beginning to end without indulging in that religious practice of the creative writing workshop: revision. This method results in a book that reads, at times, with the bewilderment of being in love. Throughout, Can Xue focuses on the women in these affairs: how they are able to navigate them and claim agency in private life, but also how they navigate public life in the modern world. Several characters choose sex work over factory work; others flee to the countryside in the hopes of finding tradition again; some disappear underground. The novel has shades, too, of the paranoid thriller, as surveillance and gossip become one. Gossip cannot thrive in isolation, but neither can love, and the book jabs its fingers in this wound, this contradiction, in an attempt to articulate a positive vision of interconnectedness.

While it could hardly be described as a fantasia of love – its shadows are deeper than that – the novel ends, like any good romance, with a kiss.

Ian Maxton is a communist writer and critic. His work has been published in Always Crashing, Boston Review, Protean, and elsewhere.

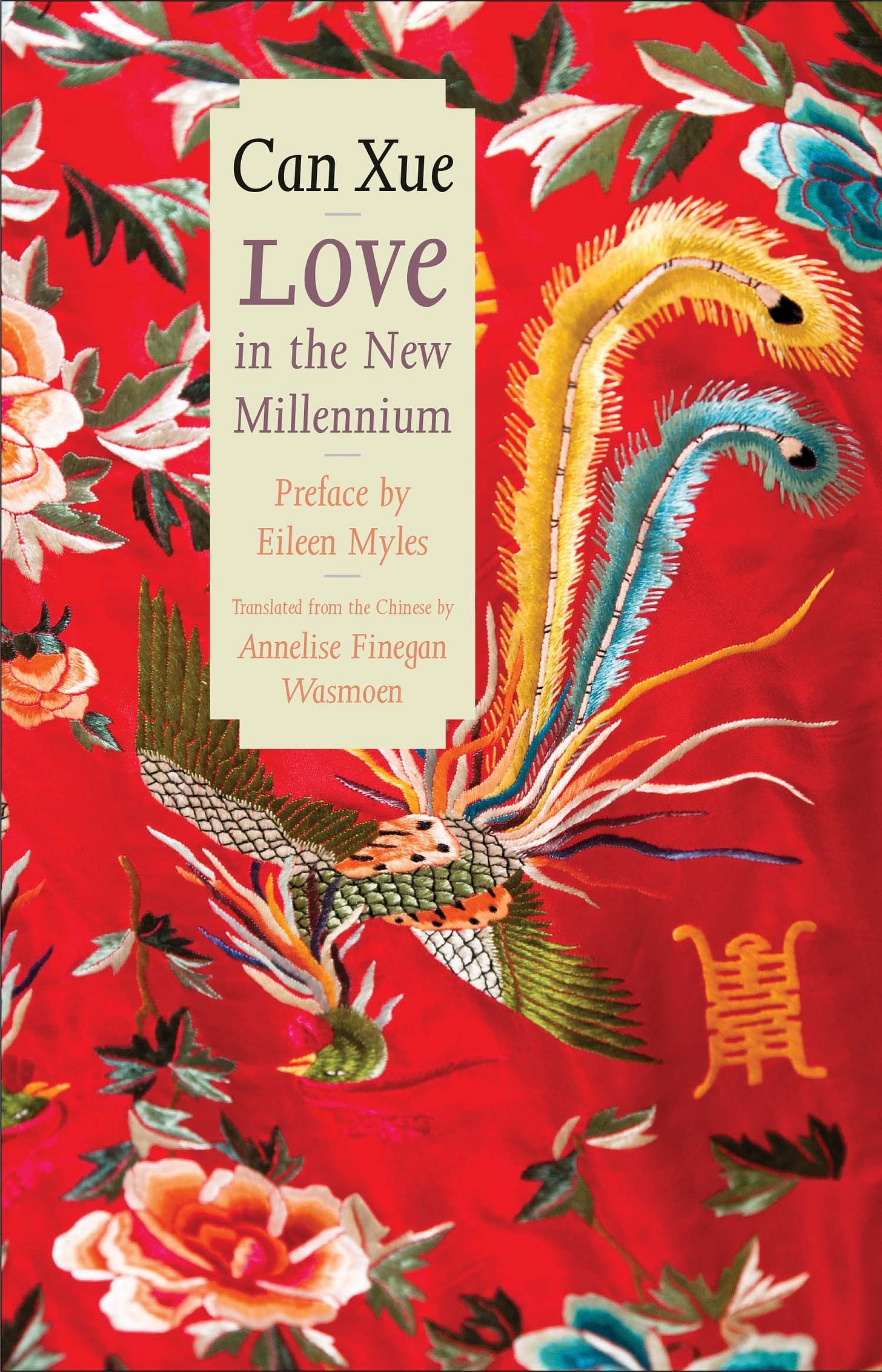

Privilege (directed by Peter Watkins, 1967)

It is lamentable that Peter Watkins’s debut feature film, Privilege (1967), is largely forgotten and to date unavailable to stream. It is also perversely befitting, because the film’s central conceit—that the mass media, government, and church could soon collude to control a restless population—would, if true, necessitate that warnings in whatever form be suppressed. I don’t suggest that the film is the victim of conspiracy, although the BBC did censor his short film, The War Game, two years earlier. Rather, Privilege is a casualty of another of Watkins’s enemies: shallow consumerism. A market that demands “dumbed down” entertainment has deemed Privilege unworthy to keep in circulation.

Privilege imagines the logical outgrowths of the then-present if things went slightly—but only slightly—wrong. Set “sometime in the near future” in Great Britain, the film concerns a pop singer named Steven Shorter (played by the real-life singer Paul Jones) who is an object of adoration of the culture at large. Shorter goes on tour across the US and UK and routinely performs in packed concert halls full of screaming teenaged girls. It’s a twisted allegorical performance from inside a cage. Uniformed cops torment and abuse Shorter as he lip-sings a melodramatic tune called “Free Me.” This abuse inevitably inspires the fans to storm the stage and attack the cops, who pretend to be overpowered, a gesture, unbeknownst to the public, of manufactured catharsis. The film, like all of Watkins’s films, is structured like a docudrama, with calm voiceover narration supplying crucial details: “There is now a coalition government in Britain which has recently asked all entertainment agencies to usefully divert the violence of youth to keep them happy, off the streets, and out of politics.” The riots are contrived to allow the youth to blow off steam. Meanwhile the status quo is untouched.

Privilege begins as satirical, closer in spirit to Hal Ashby’s Shampoo than to 1984. But when the powers that be realize their distraction isn’t working, they move on to Plan B: a total fascist takeover. The picture turns darker on a dime. Out come the flags and parades and the Nazi salutes. We are invited to conclude that latent fascism is ever present within liberalism, and that all it takes for it to surface is for democratic social management to fail. Watkins turns 88 years old on October 29th and through all these decades he has never wavered from this stance.

Jason Christian was born in raised in Oklahoma and is now based in Atlanta. He has written for The Bitter Southerner, Bright Wall/Dark Room, Gulf Coast, Los Angeles Review of Books, and other publications.

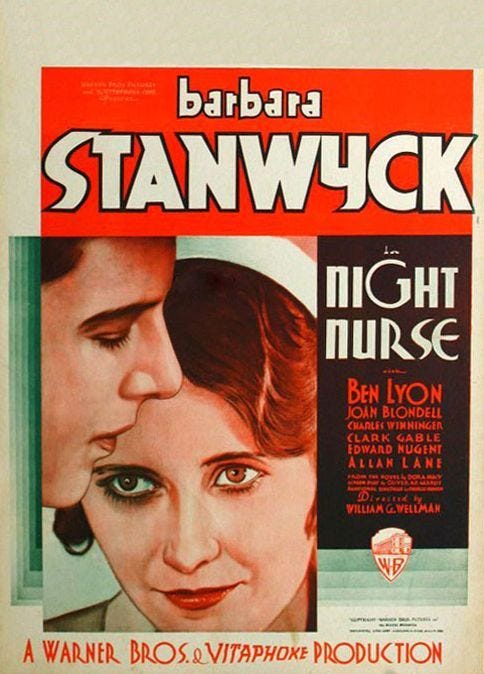

Night Nurse (directed by William A. Wellman, 1931)

William A. Wellman, even his staunchest advocates would probably admit, was an uneven director, with more clunkers in his back catalogue than some of the more prominent classical Hollywood auteurs – but it’s not for no reason that he was able to work steadily for more than 30 years, and his slender, unassuming Barbara Stanwyck vehicle Night Nurse just might be one of the finest of all the pre-Code talkies. The loose, saucy first act first gives us the “the hospital” as both a melting pot and a liminal space – a baby is born, a grown man dies, an Asian family bickers in the same room as a prim old white woman’s son, and “screens are not allowed”. A place in constant flux, where rules of class society aren’t quite so strictly enforced, and the workers crack jokes to keep from cracking up. We also come to see that the “politics” of the hospital are always really sexual politics – Stanwyck gets her job despite lacking qualifications because a powerful doctor old enough to be her father takes a fancy to her; a bootlegger can avoid a state-sanctioned beating if the nurse treating his bullet wound is smitted by him; “doctors never marry nurses, but interns do”.

As Stanwyck earns her stripes the film grows up with her, becoming darker, more serious, confronting us with ethical dilemmas that, suddenly, don’t have such easy answers. She finds herself working for a corrupt “society doctor” (who twitches so much they might as well just show him snorting lines on screen) involved with a perverse inheritance scheme that necessitates the elimination, by slow starvation, of two young children, the beneficiaries of a trust fund that their widowed “socialite” mother, who lives one of those glamorously abject lives seen only in pre-Code Hollywood, would much rather spend on champagne and forgetting. This could easily be too much tonal whiplash for such a slight film, but it works because the essential subject remains the same: the power dynamics of a particular institution – now a dysfunctional bourgeois household rather than a hospital – as seen from the perspective of a newcomer with minimal power to influence it, i.e., Stanwyck. We see the never-ending party the Mrs. is drowning herself in, we see the constant, looming threat of sexual violence that comes with it, we see the anguish of the old housekeeper who can tell what’s going on, and the brutality of the chauffeur who’s cooked up the twisted scheme in the first place – and all the while the children grow weaker in their dreary sickroom, just down the hall from the laughter and debauchery. The movie has a happy ending, of course, it’s not that heterodox, but it’s a happy ending that comes with a murdered corpse. A child grows up, a grown man dies – screens are not allowed.

David C. Porter is a writer and photographer from upstate New York. His work has appeared in surfaces.cx, Apocalypse Confidential, BRUISER, and other publications. He also publishes on his own platform, Garden Scenery. His hybrid collection A Hollow Shape is available now from Feral Dove Books. He can be reached on Twitter @toomuchistrue or via his website.

Project X (directed by Nima Nourizadeh, 2012)

Like other Phillips productions, Project X uses the same era of Hollywood R-rated comedies as not even baseline but template (think from Carter to Reagan era Americas). Produced and released into Obama’s second administration, arguably a peak of neoliberal capitalism and mass surveillance, digital media allowed for unknown levels of interconnectivity and disconnection. Project X, with its post-Fordist editing and found footage presentation divorced from their past use in the horror genre (Blair Witch Project, Cloverfield, Paranormal Activity film series), it deploys a variety of both recorded and live streaming media (first Dax recording, later oscillating between flip cell phone footage caught by spectators of the chaos, police dashcam footage, local live reporting) in the realm of comedy using the skeletal framework of the bog standard “teen party gone wrong” narrative (providing some sense of structure, beginning with the opening text card both thanking and apologizing to the citizens and police personnel of North Pasadena). It’s faux realism not unlike the plethora of online media on sites like YouTube that had the whiff of “is this real or staged” (the film cast largely unknown actors, ignoring the pop-up appearance of Simon Rex, which even then brings an unexpected level of authenticity as he’s been a staple/hang around stretching back to ‘90s MTV). With director Nima Nourizadeh, each cell capture frees the denizen to partake in the instantaneous bliss afforded through amateur captures, 5 seconds, 10 seconds, delivered in bite sized increments and from any sense of collective responsibility and moral gravity. Sousveillance, this isn’t. The destruction of upper-class Obama-era suburbia induces momentary euphoria, but not liberation. What's burnt will be rebuilt. Gen X nihilism through millennial affectation.

Take the police body cameras meant to produce accountability. Their periodic release to the public, often by outcry, while does reveal the true purpose of the police state (property protection), doesn't affect any material change. It manifests as a mainly voyeuristic exercise, the typical liberal feeling of disgust/arousal from the captured violence. Preservation is maintained, and what's captured serves as no more than a kind of sexual release for the white, cis-het spectator who's only relation to such violence is from the theater seat or transmitted in their gatekept communities. When we witness CCTV footage it's when the film oscillates between civilian and state media captures. The effect produced is an implicit sense of alignment, and understanding, between the public and the state.

The film ends with an exchange between a news anchor and Costa (the organizer of the party). Sitting behind her news desk, Costa standing in some nondescript neighborhood, the anchor asks if he wants to apologize (not before prefacing the block party as "the most epic party of all time"). Not only does he refuse to does he promise to create another. Costa has already moved on and is looking for that next sense of gratification. It’ll last seconds, sure, and it won’t last. And after that? He hasn’t thought that far ahead. And why should he? He’ll be fine.

Dana Aklilu runs the substack Vacant Lots.

"And why does child Ernesto refuse to learn what he doesn't know yet?"

"Because it's not worth learning."