The Hobbyhorse's Capsule Spotlights: Vol. 3

On Jane Schoenbrun, Fred Camper, Leighton Pierce & David Ayer

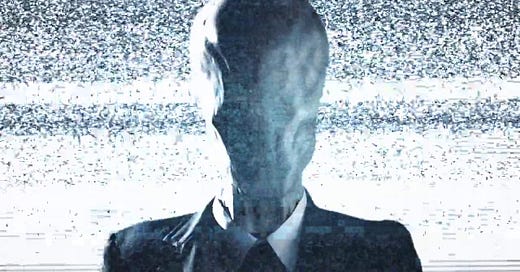

A Self-Induced Hallucination (Jane Schoenbrun, 2018)

A Self-Induced Hallucination could easily be the title of Jane Schoenbrun’s breakout film, We’re All Going to the World’s Fair—which they were writing while compiling this documentary—but their novel first feature, made entirely of found YouTube videos about the Slender Man, is not just a precursor or a companion to its more well-known fictional sibling. Though they share many themes and are both fundamentally about the occultic way the internet blurs reality: that its performative content, in this case acting like one believes an internet campfire story because they are usually told from a first person point of view, will echo with the repercussions of reality, often back through the very person who was, or at least thought they were, playing pretend.

But there is something of Adam Curtis in Self-Induced Hallucination’s provocative contrast, cutting from an Epic Rap Battle between Slender Man and Jeff the Killer to news footage of the two young girls who tried to kill one of their friends, stabbing them nineteen-some times, in honour of this internet myth that started as an entry in a forum’s photoshop competition. He only really became something more when videos were made, however credulous or performative, trying to debunk him.

World’s Fair follows its protagonist into this world of internet magic and delusion until she dissolves or escapes, depending on how you want to read the ending, while Self-Induced Hallucination continues onwards. Tacky internet media is brought into the real world in this profound and violent way, but then is digested back into content, re-fictionalised whether through literal accusations that the girls were crisis actors, a gauche television recreation (during an interview for which the precarious young star gets lost between real names, fictional names and actors’ names), or, of course, the news. The film’s most haunting image comes when a clip of a police interview with the real-life attacker fades to the ABC News logo and a large, low-quality picture of the subscribe button. The play symbol within it blinks, hypnotic and desperate, begging you to click it, to keep watching, to fall deeper into this cycle.

Esmé Holden is a trans woman and a writer currently based in Manchester, England. She has written for Little White Lies, Cinema Year Zero and In Review Online, amongst others.

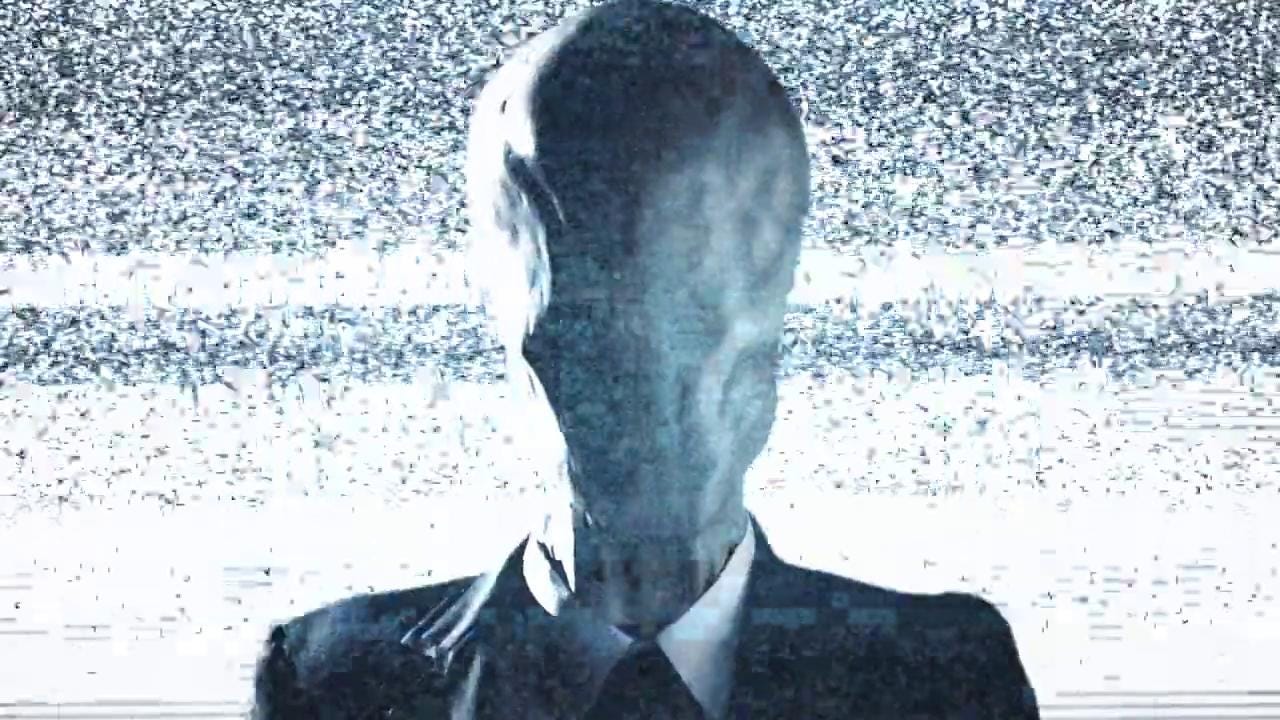

Fred Camper’s Short Films

Some of the best, most fascinating moving images I saw last year weren't screened at a film festival, aren’t available on any streaming service, and will likely never be released on any home video format. They exist entirely for free, online, nestled in the crevices of an artist’s website. As such, they weren’t mentioned in any year-end accolades. This, then, is an attempt to rectify that, however modestly. A longtime contributor to the alt-weekly Chicago Reader, and eminent Stan Brakhage scholar (Camper is largely responsible for ushering the Criterion By Brakhage collection into existence), Camper is also a filmmaker.

His earliest works, shot on film and largely unseen since the 1970s, have recently been restored and screened; after working in still images, photography, and conceptual cut-outs for the last 20-odd years, Camper has embraced video as a viable mode of production. As of this writing, his Interactions series consists of 12 individual shorts, although the series can be added to indefinitely. They range in length from 4 to 9 minutes, each filmed at a particular place Camper was visiting. Several are named after their place of origin—Interactions 1: Denver; Interactions 6: Amsterdam, and so on. Others are more specific, like Interactions 10: Paolo Uccello’s Hunt, titled after a painting, or more vague, like Interactions 3: Forest and Stream and Interactions 12: Both Sides of a Street. The videos share some commonalities yet also diverge in fascinating ways, and watching them individually versus en masse reflects the complexities of even these seemingly simplistic objects.

1, 4, and 6 consist mostly of street scenes: pedestrians stroll past the camera, as do cars, buses, and trains. Camper tends to emphasize the natural geometry of objects—panning horizontally to follow the trajectory of movements, or tracking up alongside a tree trunk or tall building. The camera largely conforms to what the human eye would do in such situations. 2 and 3 are constructed differently; there are no human figures or buildings, only closeups of plants, trees, and the natural textures of the forest (although a dog makes an appearance in 3). All of the videos are shot hand-held, and while “jittery” would be too strong a word, the subtle shaking of the image makes the viewer constantly aware of the artist behind the camera. Interactions 5: Netherlands Skies becomes something else altogether, as Camper cuts between paintings in a museum and the sky itself at various stages of the day. The juxtaposition seems clear enough, conflating the act of looking at a piece of art with the inspiration for that very art. He goes a step further with 10, filming the titular painting not as a whole but as splintered fragments, then juxtaposing those shards with images of teeming crowds outside the museum campus. What becomes clear across all 12 of the shorts is that we are witnessing an attempt to arrange a specific way of looking. As Camper puts it in an artist's statement, his work is all about “looking at the world.” There is no philosophical difference between urban areas, nature, or paintings, all are absorbed by the viewer and rearranged in an effort to make sense of the world around us.

Part diary films, part travelogue, Camper’s art exists in a continuum with Brakhage’s, of course, but also Mekas and Baillie. For lack of a better term, we could call these lyrical films, which P. Adams Sitney suggests “replaces the mediator with the increased presence of the camera. We see what the film-maker sees; the reactions of the camera and the montage reveal his responses to his vision.” Or, back to Camper’s words, about looking. These are unassuming shorts, deceptively simple, but as William Gass said of simplicity, “… refinement requires leisure, judgement, taste, skill, and the patient work of a solitary mind passing itself… back and forth across an idea.”

Daniel Gorman lives and works in the northern suburbs of Chicago. A long-time staff writer at In Review Online, you can find him on Twitter to talk about movies @danielgorman20.

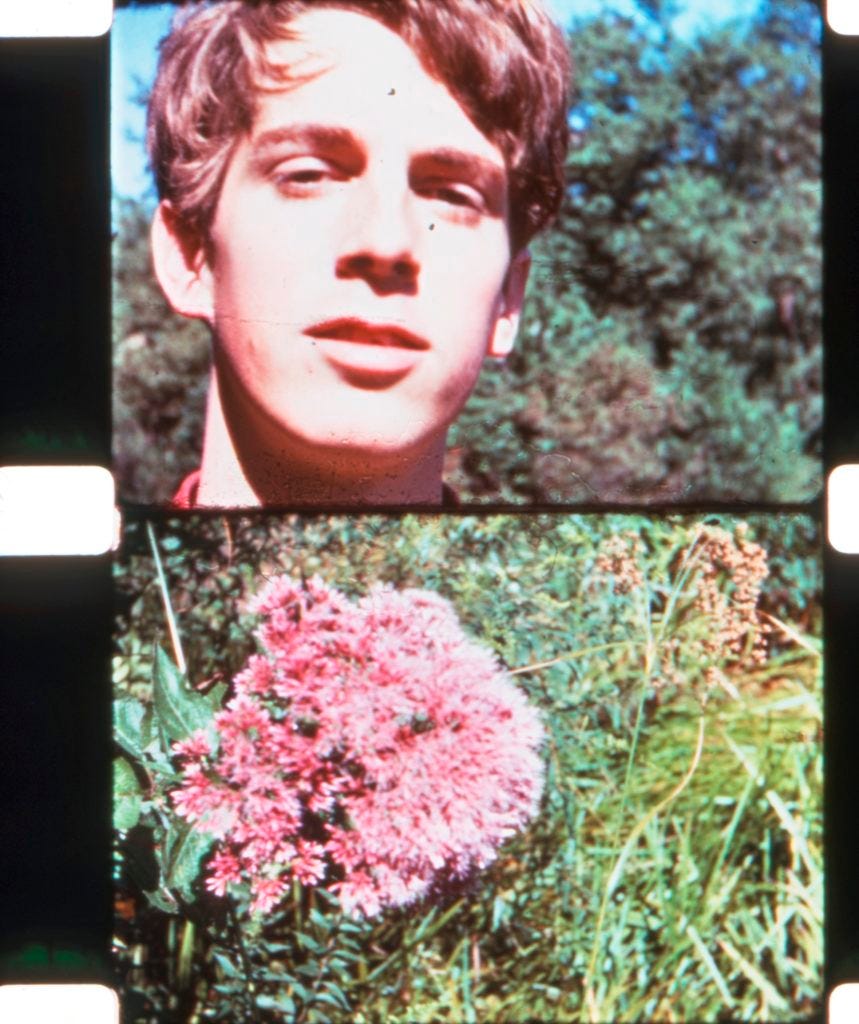

50 Feet of String (Leighton Pierce, 1995)

With its seasonal work cycle and relative insulation from the harshness of the profit-motive, academia (at least as it existed in the latter half of the 20th century) has been the shelter of choice for many artists of considerable talent, but negligible commercial potential. Some of the most important filmmakers of the post-war era, pivotal figures like Stan Brakhage or Peter B. Hutton, spent a much of their lives teaching, as did, on the other hand, hundreds or thousands more whose work is virtually unknown, except to those who learned from them how to be filmmakers themselves. Somewhere in the middle of this spectrum is Leighton Pierce, previously of the University of Iowa, more recently Dean of the School of Film/Video at CalArts. Pierce’s work is not entirely "obscure" these days—it’s been shown at major museums and film festivals, you can find some write-ups on him with a quick search. But unless you’re seriously interested in “experimental” (whatever that means) cinema, it would very easy to miss it entirely. Which is unfortunate, because it's often astonishing.

In 50 Feet of String (1995), a 52-minute film which, in an oeuvre consisting mostly of shorts running somewhere between 3 and 15 minutes, can be considered something like a magnum opus, Pierce's primary tool is the extremities of rack focus, moving the focus plane between subjects positioned generally in the "close" to "very close" range, with an extremely shallow depth of field. Shallow depth of field is often the first resort of lazy filmmakers unprepared or unwilling to deal with photography's profusion of visual incident, but Pierce’s usage is different, because it's not a shortcut for him—in his compositions, what's not in focus is just as important as what is, and their relationship is anything but deterministic. The colorful handle of a plastic shovel, a basket of flowers out on the porch, a billowing curtain, a swinging door—tightly, intimately framed, bathed in hazy light and diffuse shadow, the images often exist on the edge of pure abstraction, one slight lens adjustment away from slipping into gauzy 16mm obscurity. The sound design keeps us grounded, helps us understand where we are, what we should feel is happening: footsteps on floorboards, wind, rain, passing cars, the buzzing ambiance of lazy summer days. Domestic sounds, suburban sounds, sounds of midwestern childhood—much of the film is spent close to the ground, a child’s perspective, one still capable of being fascinated by the American quotidian. And throughout (the film is divided into twelve parts with names, uncapitalized, like "white chair" and "two maples"; much like the film as a whole, these divisions don't feel exactly arbitrary, but they feel more like suggestions than demands) runs the titular string, reappearing in all sorts of locations, always stretched taut between somewhere and somewhere else, it's never too clear. A drip from a leaky faucet falls on it and produces a deep, sonorous vibration. There is an everyday mysticism to this—a mysticism of backyards and telephone wires. Here is something, and here is something else—now, watch how one disappears into the other, and the other into the one. The grid of a screen window can be like a whole world, or it can be like it isn't there at all.

David C. Porter is a writer and photographer from upstate New York. His work has appeared in surfaces.cx, Apocalypse Confidential, BRUISER, and other publications. He also publishes on his own platform, Garden Scenery. His hybrid collection A Hollow Shape is available now from Feral Dove Books. He can be reached on Twitter @toomuchistrue or via his website.

Fury (David Ayer, 2014)

One could be forgiven for granting David Ayer definitive “hack" status. The Beekeeper notwithstanding, Ayer’s last decade has been defined in its best moments by humdrum VOD action kitsch, and in its worst by an orc cop movie we’re all still trying to forget. But ten years ago, Ayer delivered the best film of his career with the tank-bound WWII actioner Fury. Grisly, nihilistic, and helmed with a staggeringly unsympathetic eye toward the fighting men of the Greatest Generation, Fury is an impressively grim work that deserves to be counted among the best war films of the 21st century.

The year is 1945 and facing a Nazi war machine that has mobilized every man, woman, and child in an act of desperate escalation, the Americans are soon-to-be victors in name only. An army in extremis, they are badly worn down by the oppressive horrors of combat, now facing the most brutal chapter yet.

The crew of the titular tank Fury are led by Brad Pitt’s sergeant Don “Wardaddy” Collier, supplemented skillfully by committed turns from Michael Pena and Shia LaBeouf, but it’s Jon Bernthal’s hillbilly gun-loader Grady “Coon-Ass” Travis that steals the show. Bernthal plays Grady with an impressive conviction, endowing him with both a bestial spontaneity and an unyielding loyalty to his crewman. The actors spit curses, prayers, and platitudes at one another in equal measure, and their methodical attention to the cadence and temperament of these characters is the film’s greatest asset.

Ayer structures Fury with an archetypal sensibility that anyone who has seen Saving Private Ryan will find familiar. Fighting men go on a mission into the belly of the beast, sustain casualties, and ultimately—outgunned and outmanned—make a daring last stand. Along the way, Fury even cribs its audience surrogate from Ryan, with Logan Lerman’s babyfaced Norman conscripted from his gig as a typist to a seat in the Fury as a bow gunner. His boyish features will soon be caked under a layer of blood and dirt, the glint in his eye slowly glassing over into a thousand-yard stare.

Unlike Spielberg’s film, there are no heroes here. The crew of the Fury play their parts not as upstanding bastions of moral clarity, but as tactless roughnecks in each other’s company and unrepentant executioners on the battlefield. They approach combat with the callous detachment of bone-weary laborers. In the brief pockets of calm, the refrain, “Best job I ever had” offers not only a vital renewal of fellowship amongst the men, but a collective spiritual cleansing; pardon for their brutality and permission to do it all again.

The real showstopper occurs in the unnerving quiet of brief, feeble domesticity. After taking a German village, Don and Norman enter the apartment of a woman and her younger cousin. Unable to protest the intrusion, the soldiers take the opportunity to rest, wash, and—in Norman’s case—engage in intimacies with one of the women. It’s a knotty scenario, as the men exploit the inherent power dynamics at play. And yet, there’s no indignity to it; no ugliness or shame from any party. Ayer directs the scene with uncharacteristic patience, allowing the complexities of each imposed role to play out. It isn’t long before the remaining members of the crew crash the idyllic scene of respite. Drunk and quietly outraged by their exclusion, they act out, charging the scene for the first time with a real threat of peril. It’s an electric scene, and one that never moves quite as you might predict. It also epitomizes the film’s dour thesis: This homemaking is a brittle fantasy. These men no longer belong to this world, but to perdition; doomed to torment and brutality for the remainder of their short lives.

Aaron Casias is a San Francisco-based podcaster and film critic. He is the producer and co-host of Hit Factory Podcast, exploring the films of the 1990s from a (mostly) nostalgia-free perspective, favoring a deep analysis of production history, sociopolitical context, and the ways these films continue to speak to the media landscape of today.