Like nearly everyone who reads, I possess a certain set of political beliefs and principles. And like nearly everyone who reads, I read the work of writers with whom I broadly agree on political matters — and some writers with whom I disagree on those matters, some generally and some profoundly. Which isn’t to say that it’s a litmus test for my own reading; I’m happy to read the works of Saul Bellow or James Ellroy, whereas I’m increasingly wary of reading anything new from Orson Scott Card or Dan Simmons. It’s the difference between reckoning with political themes in one’s fiction and turning works of fiction into something much more didactic. I’m always game for the former; I’m actively hostile to the latter, even if it comes from a writer whose (left-wing) politics are much closer to my own.

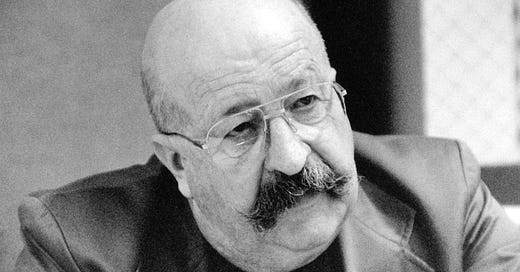

Which brings us to the question of the late Gene Wolfe, considered (correctly, in my opinion) to be one of the 20th century’s greatest writers of science fiction and fantasy, and to some one of the greatest writers, full stop. Wolfe described his own politics as conservative in an interview with the National Review’s Between the Covers podcast in 2009. A visit to the political donation database OpenSecrets revealed that Wolfe — or someone who shared both his name and lived in the same Illinois towns that he did — made donations in the 2010s to conservative politicians Greg Abbott and Tom Tancredo.

With the publication this year of a new collection of Wolfe’s shorter work, titled The Wolfe at the Door, I was left wondering: to what extent did Wolfe’s politics make their way into his fiction? That the introduction to this volume is by Kim Stanley Robinson — who spoke of the importance of social democracy and democratic socialism in a 2022 Jacobin interview — is an initial sign that the answer to that question might be, “Not much.” It might be more apt to say that Wolfe’s political leanings are occasionally present in his work if you look very closely — but he’s much more prone to follow a given story wherever it might lead, political implications be damned.

Wolfe’s 1988 novel There Are Doors follows the travails of Mr. Green who, when the novel begins, is conversing with his paramour Lara. A line of dialogue opens the book: “Do you believe in love?” Quickly, two things become apparent. The first is that Lara is being evasive, telling Mr. Green (who believes otherwise) that “I am not a woman” as the two engage in some heavy petting. The other is a line that makes little sense when you first read it; like nearly everything Wolfe wrote, seemingly offhand comments turn out to be much more significant on a second reading. In this case, it’s something Lara says:

...and then the men die. Always. She holds his sperm, saves it, and bears his children, one after another for the rest of her life. Perhaps three children. Perhaps three dozen.

The two lovers go their separate ways, and Mr. Green’s search for his lost love occupies the rest of the book. Turns out Lara wasn’t lying when she said she wasn’t a woman; instead, she’s a goddess, and one who lives on a parallel world. And it’s there that her earlier remarks about men dying in the act of sex come back to haunt the narrative. Or, as one woman on the parallel earth explains to Mr. Green:

But when you’ve fulfilled your biological destiny—when either sex has fulfilled its biological destiny, actually—it dies. That means sixty or seventy years for us, sometimes only fifteen for men.

Especially given the way sex and gender have been discussed in many conservative circles in the last few decades, you might think that a world in which biology is destiny would be almost utopian for Wolfe. Spoiler alert: in this case, it is not. While Lara’s world is largely presented as comparable to our own — with its own politics, its own espionage, and its own approach to medicine and technology — there’s also one brief aside that leaves Mr. Green (and, by extension, the reader) shocked: this alternate United States is one where slavery has thrived. And while the novel largely confines itself to Mr. Green’s perception, an alternate world where slavery is okay is a pretty large red flag that all is not well.

Reading There Are Doors, I was reminded of the subtitle of G.K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare. While these two novels are quite different, there’s something of the nightmare to There Are Doors as well; a sense that Mr. Green’s pursuit of his lost lover is also a voyage into a world where his own neuroses and anxieties are given form.

Both There Are Doors and 1984’s Free Live Free are relative outliers in Wolfe’s 1980s output. That decade also saw the release of his (deservedly) classic Book of the New Sun, the Soldier trilogy, and The Urth of the New Sun, the ecstatic and mystical follow-up to the former. Free Live Free and There Are Doors are largely set in the then-contemporary United States, which might provide Wolfe with the opportunity to weigh in on political matters. By and large, he does not do so.

The characters in Free Live Free are a group of people living on the margins of society, including a salesman, a sex worker, and a private detective. They live in a condemned building owned by one B. Free, an elderly man of mysterious origins. The characters are rendered with relative empathy; the terse wording of the classified ad that brings them together, including the phrase “Hlp sv hs” — an abbreviated “Help save house” — is one of the more sentimental aspects found in Wolfe’s bibliography.

If Free and his tenants have an adversary in the novel’s early pages, it’s the Building Commission that has ordered the demolition of their building — and while there is something vaguely libertarian about this plot point, it doesn’t feel heavy-handed. Gradually, that conflict gives way to something greater: the disappearance of Free and his former tenants’ discovery of a conspiracy that extends incredibly high off the ground. This is both figurative (one character refers to the nation’s “key people”) and literal (a massive plane in perpetual flight plays a role). Governmental surveillance and military and intelligence agencies also play a large role here, with the FBI occupying an antagonistic position in the book’s denouement. (If this sounds somewhat vague, that’s intentional; the details of what, precisely, is happening in Free Live Free are best experienced by reading it.)

Returning to The Wolfe at the Door, it’s worth mentioning one of the most striking elements of Kim Stanley Robinson’s introduction is a moving account of Wolfe’s PTSD stemming from his participation in the Korean War. “[O]ur culture is awash in cheap and stupid fake violence, which often leads to real violence and all the real pain that follows. It can wreck people’s lives, that grotesque careless stupidity,” Robinson writes. “Gene wasn’t like that. He knew the real thing.” And there is a profound empathy that runs through much of Wolfe’s fiction — one that seems eminently aware of the fragility of life, even if it sometimes makes a wry comment about it.

Wolfe’s short fiction includes a few deeper forays into the inner workings of politics. A few can be found in his 1980 collection The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories and Other Stories, including a starship captain speaking approvingly on the British navy’s system of training officers in “Alien Stones,” and in “The Doctor of Death Island” which includes a prison warden explaining the current state of society to a convicted killer who’s recently become functionally immortal:

Our country is locked in a paradox. It is necessary that the people believe that they have the right of ownership of property, ideas, and so on—you have to understand that. Yet at the same time, it is vital that the government and the extragovernmental corporations—those whose assets exceed half a billion, let us say—have access to the actual real estate, inventions, or whatever. Thus we have laws of eminent domain, and so on.

That said, the story is less concerned with this turn of affairs as it is with the immortal murderer at its heart, and how he reacts to the paradoxical situation he finds himself in: revived with a dramatically extended lifespan, yet also incarcerated.

This collection also includes “Seven American Nights,” about an Iranian man who travels to a United States in decline and becomes embroiled in a bizarre and potentially earth-shaking conspiracy. Here, Wolfe depicts some of the raw materials of American patriotism and nationalism as having curdled into something sinister. Presciently enough, there’s a scene in this novella in which the story’s narrator encounters an impoverished man who says, of his nation, “Someday we are great again.”

Politics appear briefly in the 1988 collection Storeys From the Old Hotel: the society depicted in “Sonya, Crane Wessleman, and Kittee” is one with a universal income, for instance. But the range of stories here feels a bit more playful than its predecessor; while there are serious explorations of humanity’s place in the world, there are also adventure stories and a Sherlock Holmes pastiche or two. The Wolfe at the Door has a similarly wide-ranging approach; the stories (and a few poems) represent the full breadth of Wolfe’s career, and cover everything from nods in the direction of Borges and Proust to Wolfe’s forays into crime fiction.

Still, there are a few stories that reckon with political matters, including a subplot about labor relations in “The Gunner’s Mate,” a ghost story set on a tropical island; and the fractured society of “The Green Wall Said,” about humans hearing from another intelligent species. If there is an ideology to be found in The Wolfe at the Door, it’s one with a widespread empathy extended towards all. Or, as a restless spirit based in a kind of purgatory tells the story’s narrator:

“Am I making this clear? All of life is a big, big game made up of little ones, with everybody playing on the same team. Do I have to explain who and what you living people are playing against? Entropy is one of their names.”

It’s probably worth saying here, too, that there’s a mention of Leon Trotsky here. It comes in a story called “Easter Sunday” about an encounter between Reverend Dobson — “a religious man with no hint of fear in his love of God” — and a stranger. Or rather, a Stranger, as Wolfe uses a very significant capitalization in his description of the man Dobson encounters, who tells him a tale of exile:

My country was a dictatorship. He calls it a kingdom now, and plans on his son following him, but you must understand that there is no established line preceding him. … The peasants are taught that to doubt him is the most hideous crime. In fact, in the last analysis, it is the only crime.

The minister inquires as to the nature of the Stranger’s schism. “Tell me, sir, are you a Trotskyist?” The Stranger responds in the negative, telling the Reverend that “my rebellion greatly precedes Trotsky’s.” The two men part ways, and the final line makes it fairly clear that this political exile is, in fact, Satan.

And yet the way in which he phrases the terms of his exile evokes more sympathy than anything else; the notion of Lucifer as a revolutionary-turned-dissident in an absolute monarchy is an unexpected spin on Paradise Lost, but it’s also deeply felt. And if Wolfe’s empathy is broad enough that it can encompass the actual devil, well, that’s a quality with which it’s hard to argue.

It’s also a moment that, once again, echoes the work of G.K. Chesterton, such as this line from What’s Wrong With the World: “The really courageous man is he who defies tyrannies young as the morning and superstitions fresh as the first flowers. The only true free-thinker is he whose intellect is as much free from the future as from the past.” And it should be said that that is no coincidence. In a 2014 interview with MIT Technology Review, Wolfe spoke of Chesterton as one of his two main influences. When asked what specifically appealed to him about Chesterton, Wolfe’s answer resonates deeply across much of his own work: “His charm; his willingness to follow an argument wherever it led.”

That quality may help explain the deeply felt political leanings of Gene Wolfe and the relative absence of them from his fiction. Like Chesterton, he sought to follow the argument which took him to countless places, from ancient Greece to Earth in the distant future to a secret military plane flying miles above the ground. Where it did not take him was the realm of didactic arguments or ready-made platitudes—as readers, we’re all the better for it.

Tobias Carroll is the author of four books to date. A new edition of his collection Transitory is out now on 7.13 Books; in early 2024, Whisk(e)y Tit will publish his third novel, In the Sight.

"Easter Sunday" was one of the first, if not the very first, stories Wolfe ever published: It appeared in his college paper in 1951!

(Yes, I know "The Dead Man" is usually cited as "the first Wolfe story," and it may well have been the first one he was paid for.)