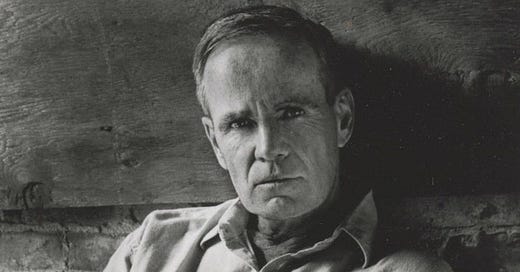

A famous author’s death is a surreal one. Less an occasion for discovery, as with more obscure or niche authors, the famous author’s passing invites remembrance, even eulogy. As with more private funerals, mourning tends toward the snapshot: highlights of their work, anecdotes, and photograp

hs of what they looked like throughout their career, all collaged together. Decades of life, collapsed into space.

Cormac McCarthy, who died on the 13th of June, has been widely remembered and thoroughly eulogized. Refreshingly, it’s McCarthy’s prose that readers tend to remember—his style. In the New Republic, Alex Shepard referred to the “singularity” of McCarthy’s sentences, “which ricocheted—sometimes gracefully, sometimes jarringly—between gruff matter-of-factness and soaring, biblical grandiloquence. His style married Hemingwayean bluntness with the transcendent beauty (and sometimes ridiculousness) of The King James Bible.” In the New York Times obituary, Dwight Garner quotes Saul Bellow, who referred to McCarthy’s “absolutely overpowering use of language,” as well as critic James Wood who called him “a colossally gifted writer” sometimes erring “close to nonsense.” In the Financial Times, Christian Lorentzen noted the pastiche of his style, combining “the declarative directness of Hemingway, with the baroque inflections of Faulkner, comprising allusions that stretched from Beowulf and Shakespeare, through Melville and Hawthorne, up to Robert Frost and Allen Ginsberg.” Even on social media, where users shared passages from several of his books, McCarthy’s prose itself seemed to be the primary aspect of his career as a novelist.

Along with violence and a lack of women, McCarthy’s prose also tends to be the serial complaint about his books. Overwrought, it gets called. Ridiculous. Tortured. Strangely, for a writer so lauded for his sentences, the sentences themselves—taken out and shown to others—often lose their allure. They might ravish on the page, but transcribe the paragraph and give it to someone who’s never read his books and often they’ll say anything between “I don’t get it” and “This is terrible.” Typically, this too appeared on social media: widespread mockery of some of the most arresting passages in contemporary American literature.

This contention has always haunted McCarthy’s work. While other novelists with long careers, extensive bodies of work, and extraordinary depth (Toni Morrison, Don DeLillo, Louise Erdrich, Denis Johnson, Marilynne Robinson, Leslie Marmon Silko)—novelists whose prose, atop their overall genius, is nonetheless singled out for its texture, its poetic invention—there is rarely anything to quibble over in their sentences, even when photographed or otherwise excerpted. It’s always evidently good writing.

In the case of most younger (American) novelists—along with a few troublingly influential and easily misunderstood writers (Raymond Carver, Joan Didion, David Foster Wallace)—the excerpts, when they appear, are just evidently writing; the sentences themselves seem ready for the close up, their beauty and their craft carrying the hours spent plucking and exfoliating themselves in the mirror of the writing workshop. They tend toward the more derogatory use of the word “style”—that facile opposition to “substance.” But both Carver and Johnson excerpt beautifully; and, in a literary culture increasingly digital, they circulate accordingly. They circulate because all these writers, first rate or not, build their fiction with the unit of the sentence, or (in Morrison’s case especially) the paragraph. It fits in a frame.

McCarthy’s language does not fit in a frame. In his novels, the unit is not the sentence. It’s not even the paragraph. The novel, for McCarthy, is what the novel is made of. This places him in a different category of stylists—with David Markson, say, and Thomas Bernhard. Clarice Lispector. José Saramago. Even Samuel Beckett. While these writers wield exquisite control over their sentences, the sentences serve their novels in a way many other writers’ do not—which consequently makes it difficult to clip sentences free and use them as digital currency. Their skill is not recognizable at a glance.

Pages from these novels, in a phrase, do not photograph well. This is the first major aspect of McCarthy’s style.

***

Let’s have a look. In Suttree, one of his two finest novels, McCarthy describes rainfall on a river running through Knoxville: “Small spills of rain had started, cold on his arm. Downstream recurving shore currents chased in deckle light wave on wave like silver spawn. To fall through to darkness. Struggle in those opaque and fecal deeps, which way is up. Till the lungs suck brown sewage and funny lights go down the final corridors of the brain, small watchmen to see that all is quiet for the advent of eternal night.” Editing or critiquing a manuscript like this, you’d likely write “too much” in the margin, “too heavy,” “too reaching”; but in Suttree, there’s at least two or three too-muches on every page. Aired out by scenes of conversation—long strings of skinny, often hilarious dialogue—the whole book otherwise reads like this, the fecal and the divine whirled together in the novel’s current. Generally, adjectives and nouns are what charge the novel—the “deckle light,” the “silver spawn,” the “final corridors,” the lungs and the sewage and the watchmen. It’s a generative prose that recalls (as Lorentzen suggests) Robert Frost:

Speaking of contraries, see how the brook

In that white wave runs counter to itself:

It is from that in water we were from

Long, long before we were from any creature.1

Cleaved, however, “opaque and fecal deeps” sounds like someone’s colon; “the lungs suck brown sewage,” a punk band; “the advent of eternal night,” a tired echo of Wordsworth or Coleridge—beneath, frankly, someone who’s lived in Melville, in Shakespeare. A pan of rank riverwater without the rippling of the river, undrinkable. Untenable.

In Blood Meridian, his other finest novel, the motion of the prose isn’t generative or dynamic. If anything, it’s degenerative:

In that cold stable the shutting of the door may have evoked in some hearts other hostels and not of their choosing. The mare sniffed uneasily and the young colt stepped about. Then one by one they began to divest themselves of their outer clothes, the hide slickers and raw wool serapes and vests, and one by one they propagated about themselves a great crackling of sparks and each man was seen to wear a shroud of palest fire. Their arms aloft pulling at their clothes were luminous and each obscure soul was enveloped in audible shapes of light as if it had always been so. The mare at the far end of the stable snorted and shied at this luminosity in beings so endarkened and the little horse turned and hid his face in the web of his dam’s flank.

No whirling current here, no tide pool for pollywogs and mayflies. Instead a long, ambling clop: a sterile predestination. While the unusual nouns and Latinate shuffling of adjectives is familiar, it’s the verbs, in Blood Meridian, that drag the novel forward: the darkness of the stable “evoked”; the horses “sniffed” and “shied” and “snorted” and “hid”; the men “propagated,” their souls “enveloped”; they “divest” their clothing.

Isolated, on the other hand, it’s hard to unsee the high camp of “a shroud of palest fire” (Shakespeare and Nabokov with one stone); the vagueness of “each obscure soul”; the sentimentality of “the little horse.” Without the novel’s two hundred or so pages preceding this paragraph; without being inculcated into its rhythm, its vocabulary; without falling in line with its march, it’s hard not to laugh it off—what melodrama! Do this over and over and you’ll realize just what a risk McCarthy took with each of his novels, and how openly vulnerable, as a stylist, he was willing to be.

This vulnerability reminds me of another writer also lauded for his sentences, and whose style is almost as difficult to “photograph.” In James Salter’s own two finest novels, A Sport and a Pastime and Light Years, the rich sensuality that colors our formative moments in life are so numerous and so hypnotizing it’s almost impossible to share them with anyone; they are as private as the acts and experiences they describe. Reading these novels, like McCarthy’s, is to be alone in a way that reading other brilliant writers often is not.

Salter loved to write a good fuck. In A Sport and a Pastime, the sex scenes approach a religious intensity: “With a touch like flowers, she is gently tracing the base of his cock, driven by now all the way into her, touching his balls, and beginning to writhe slowly beneath him in a sort of obedient rebellion while in his own dream he rises a little and defines the moist rim of her cunt with his finger, and as he does, he comes like a bull.” The prose here, in its reverence, isn’t all that different from its descriptions of shucking an oyster, of pouring a glass of Chablis, of driving past a field of lavender with the top down. But if you were to post this paragraph on social media and say “what beautiful prose,” you’d probably get unfollowed at best and, at worst, main-charactered as a misogynist.

In Light Years, shooting a load isn’t so revelatory, painted as it is with a softer, more impressionistic brush, but it is a mystic experience nonetheless. Dean of Pastime is, after all, a young man, and Viri is not: “She saw him far above her. Her hands were clutching the sheets. In three, four, five vast strokes that rang along the great meridians of her body, he came in one huge splash, like a tumbler of water. They lay in silence. For a long time he remained without moving, as on a horse in the autumn, holding to her, exhausted, dreaming. They were together in a deep, limb-heavy sleep, sprawled in it.” He came in one huge splash, like tumbler of water: not the prettiest picture, even if you do like cum.

It isn’t all about sex. There are other passages that live on the page and die clipped from context, such as a moment alone after a busy day:

They were united, all of them in the great, blue evening that reigned over the river and hills. They talked on and on. Afterward he sat with the paper, the Sunday edition, immense and sleek, which had lain unopened in the hall. In it were articles, interviews, everything fresh, unimagined; it was like a great ship, its decks filled with passengers, a directory in which was entered everything that had made any difference to the city, the world. A great vessel sailing each day, he longed to be on it, to enter its salons, to stand near the rail.

Looking at them, Salter’s sentences, out here on their own, asking for so much, is like overhearing a deeply personal, desperate prayer—the embarrassment of glimpsing someone beg God for help. This, I think, is what separates Salter and McCarthy from other writers whose unit is also the novel—the Becketts and Lispectors and Saramagos. Those writers’ novels too carry a hypnotic, mystic quality; a babbling incantation. But they’re not vulnerable so much as indifferent, even confident; they don’t want in the way Suttree wants. McCarthy’s “singular” prose is vulnerable because it wants to untangle life on earth, and there’s a sense that he felt he shouldn’t have let us see this desire—that he should have known better than to trust us. It echoes the vulnerability of James Wright’s volta, “I have wasted my life.”2 This is the second major aspect of McCarthy’s style.

***

If there is vulnerable, open prose, certainly there is defensive, closed prose. These are sentences or paragraphs you can tell, as they were written, they felt someone watching, someone waiting to comment. Wallace saturated his work—fiction and non—with geometrically dense apologies. Didion practically riveted plates of iron over every line of Democracy (1986); and the thorny, repetitive cynicism in A Book of Common Prayer (1979) makes reading it too prickly to bother. These styles were deliberate, as her brilliant and curious Play It As It Lays (1973) has nothing of those later novels’ unblinking insecurity. As for Carver, the aversion to risk in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love may have had more to do with his editor than anything, but nonetheless the book reads as neatly, as safely, as any MFA thesis.

And then there are our younger (and not so young) novelists, debut and mid-career. I don’t want to be another one of these guys, but it’s hard not to wonder if the near omnipresence of the MFA system has nurtured prose styles that favor defensive rather than vulnerable prose. After all, most American writers are trained to anticipate criticism before they write. With the workshop in mind, criticism of the work exists, willingly or not, alongside even its earliest pages. Substitute “photograph,” in this essay, with “teach,” and this seems especially revealing with respect to passages from famous writers’ novels.

As if that weren’t difficult enough, most novelists now graduate from writing with a workshop of peers living in their head to writing with thousands other writers, readers, and industry professionals living there too—a literary city that never sleeps and whose criticisms or rejections one can read or see instantaneously, at any hour. Even for the most resolute, this kind of presence can’t not have an enormous effect on the openness, on the willingness to risk, in one’s style—not to mention, made up as it is of a plurality of styles, on American literature itself.

Earlier, I used the word “surreal.” Any celebrity’s death is surreal because celebrities themselves are surreal. (And in our little world, a famous author is absolutely a celebrity.) That it mimics a funeral, with none of a funeral’s intimacy or intensity, is surreal. Almost no one remembering him, after all, really knew Cormac McCarthy.

In Max Kozloff’s essay, “Surrealist Painting Reconsidered” (1966), he gets at the core of surrealism’s “special depiction of objects,” which attempts to “[simulate] a freedom from ‘history.’” In the surrealist detachment of objects from context and from meaning, “temporary continuity, or even interval, is broken down… [into a] ‘timeless’ format: the picture rectangle.” While initially “the art of the dream,” surrealism quickly transcended this niche preoccupation and, via Pop art, began “to perceive [the] subconscious blazing away everywhere in society’s commercial artifacts.”

Surrealism, in its “dis-relation” (as Sontag called it), elevates consumer choice—the foundation of neoliberal banality. By stripping politics, topics, words, and persons of their context—their meaning and history—and equating them, leveling them, as images or objects of “interest,” surrealism opens the door to the neoliberal transformation of all things into currency. Life becomes lifestyle, a kind of totalitarian nihilism that makes the abyssal evil of the Judge, in Blood Meridian, not only quaint, but irrelevant.

I thought this was about books. Well, in this version of literary culture, it’s a sound decision, for the look of one’s public persona, to consume or to share the sentence that’s worth more, as a unit, than the one that can’t be deducted from the novel that wrought it. It’s a sound decision to teach it instead of revere it, wonder at it. This is why McCarthy’s style is impossible to mimic, despite the constant attempts; and why Didion’s, conversely, trickles into almost every personal essay that’s ever circulated online; or why the coiled, jagged, self-abrasive energy of Denis Johnson shows up in so many debut novels. It isn’t that their prose is lesser (it’s not), but it is easier—to read, to assimilate, to teach. It’s a prose you can sample. Like the bands of the ‘90s did with so many of their influences, you can take what you love and hide it (or flaunt it) in the texture of your own work, which then makes it ring or rhyme for those in the know.

I certainly don’t think there’s anything wrong with writing like Denis Johnson, one of most invigorating and rewarding American fiction writers we’ve had. As is Toni Morrison, and Leslie Silko, and so on. But I do think there is an error in rebuffing a writer of equal genius by treating his sentences as one treats theirs, trying to exchange one currency into another. This has nothing to do with the way these novels themselves ask to be read; but it does have everything to do with the way neoliberal attitudes have colonized so thoroughly what readers and writers, in this version of culture, permit themselves to think. It’s that impulse itself—to exchange—that seems so insidious. Sure, the novels are violent; yes, they’re embarrassingly short of women; but that a writer of McCarthy’s stature and originality and vulnerability could be considered to veer “close to nonsense” in his style, or to be derided for his prose the day after his death, is the kind of reactionary critique only a repressively homogenous culture could coerce from a reader. That Cormac McCarthy was here, that he formed his sensibility, that he wrote such novels, that he enjoyed his life, and that we still have his books; that he arrived, over and over, at such style, is truly so singular as to seem impossible. But it happened. And that—whoever you are and whatever you’re after—is your open invitation.

“West-Running Brook”

From “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota”

Patrick Nathan is the author of the novel Some Hell (Graywolf Press) and the book of essays Image Control: Art, Fascism, and the Right to Resist (Counterpoint Press). His new novel, The Future Was Color, will be published by Counterpoint Press in June of 2024.

Interesting read on McCarthy. On the other hand, I've never understood Slater and his writing on sex, as per your example, is hilariously awful.