“Did he really think it through?” – Henry Miller, Reflections on the Death of Mishima

In Jean-Paul Sartre’s What is Literature he opines on what divides prose from painting, sculpture and music. Famously we learn here that “poetry is on the side of painting, sculpture, and music.” The question becomes one of meaning, or rather a precision in meaning. A painting invokes, but it does not tell. “All thoughts and all feelings are there, adhering to the canvas in a state of profound undifferentiation. It is up to you to choose.” The writer is the one who, though their empire of signs “deals with meanings”, alone possess the capacity to guide the viewer.

There is, however, a strange omission from Sartre’s typology. Nowhere does Sartre mention cinema. And it is cinema that will precisely trouble these distinctions. Cinema’s movement and its speech undo the profound undifferentiation of the canvas and the ceaseless signification of the novel alike. The form of cinema cleaves Sartre’s typology apart. Its complicated relationship to writing is already evident in André Bazin’s famous claim that “cinema is also a language”, yet is it not also somewhere in the realm of painting, of the visual? Some of the great shots of cinema have the quality of the canvas, brooding and immense.

Bazin’s “The Ontology of the Photographic Image” makes another point that is absent from Sartre’s analysis. For Bazin the plastic arts begin in Ancient Egypt, not only with the preserved mummy, but the terra cotta statues entombed with it, insurance against any additional decay of the sodium preserved corpse. The plastic arts for Bazin begin with an attempt to ensure immortality, a fact which extends through to painting: “Louis XIV did not have himself embalmed. He was content to survive in his portrait by Lebrun.” This preserving function presupposes a certain realism, a certain realism that painting is relieved of once photography and cinema emerge as distinct aesthetic practices.

“I hate Jean-Paul Sartre” declares Japanese novelist Yukio Mishima in a 1969 debate with representatives of the left wing All Campus Joint Struggle Committee at Tokyo University. It appears the old joke about Paris in 1968—that of every student’s bookshelf adorned with a hefty, prominent and decidedly unread copy of Being and Nothingness—may have applied to Tokyo as well. It is unclear why Mishima, at the height of his fame in 1969, made a point of seeking intellectual combat with these young radicals. It is commonly thought that Mishima outdid his earnest adversaries in both intellectual gravitas and social grace. And yet one year later Mishima would be dead, having committed seppuku after he and four others spectacularly stormed the Japanese Ground Self Defence Force (JGSDF) HQ in Tokyo.

Mishima’s demise appears to be the principle of living one’s life as a work of art taken to its apotheosis. One might suspect a Nietzschean inspiration here, but Nietzsche’s insistence on aesthetic self-creation was never as straightforward as it seems. In Mishima’s autobiographical essay Sun and Steel (he calls it a work of “confidential criticism”) he talks of an attempt to make a “union of life and art”1 and he means this literally. His body will become an artwork as he begins to become a bodybuilder and to escape the constraining and middling world of words.

Mishima was not content to simply reverse the polarity, to go from beautiful words to beautiful bodies. His demise, by his own hand, was a meticulously choregraphed affair. His miniaturised insurrection happened the same day he finished his final novel, The Decay of the Angel, the last in his “Sea of Fertility” tetralogy. The second book in the tetralogy, Runaway Horses, focuses on Isao, who plans the assassination of several industrialists who he believes are corrupting Japanese life with decadent western influence. The book ends with Isao committing seppuku as the sun rises; “the instant that the blade tore open his flesh, the bright disk of the sun soared up and exploded behind his eyelids.”2 This is in part an attempt to valorise an old way of life: the land of the samurai, the land of the rising sun, immortalized in Mishima’s anachronistic antihero.

Mishima was also, in creating Isao, creating his own antecedent. If life and art are to collapse into each other then the word and the deed must both be set down. It is Runaway Horses that contains another famous Mishima line: “perfect purity is possible if you turn your life into a line of poetry written with a splash of blood.” Mishima had written the poetry, but now he required the drop of blood. After storming the JGSDF HQ, Mishima read out a speech from the balcony demanding the reinstatement of the Emperor. It was after this that he went inside, his task done, and cut his belly open while his second in command Masakatsu Morita attempted to complete the sepukku ritual by beheading him.

It can be easy to admire Mishima’s demise. Here is man who lived his principles, who committed to the aesthetic quality of life and who wasn’t afraid of action. Actress Akihiro Maruyama, seeing the news of Mishima’s suicide on television, claims her first thoughts were “Well done, you did it.” Mishima knew he was not going to singlehandedly reinstate the Emperor. His plan was only to die a heroic death.

In Sun and Steel, Mishima articulates a dualistic vision of the world. There is night and day, action and literature, the body and the mind. Their unification is desired but appears impossible: “Action—one might say—perishes with the blossom; literature is an imperishable flower. And an imperishable flower, of course, is an artificial flower.” The locus of action is the body. It is the arm that moves, the leg that pumps, the hand that grasps. This distinction cannot really hold up to much scrutiny, but Mishima was not much of a metaphysician.

The beauty of the body is not the beauty of the written word. The beauty of strength is confined to the body and will fade. There can be no posthumous recognition of a beautiful body. When an artwork is perfected, it is done. With the strike of the pen that punctuates the final sentence the work is completed. It may be discussed and debated and live on, but it has achieved its form. While we can and should talk about the afterlives of literature, of renewed and reinvested critical attention, no such second life is possible for the body. The moment the form is achieved the form begins to decay.

Mishima’s work is marked early on by this awareness. In Forbidden Colors, his 1951 novel of homosexual desire, there is the magnetic beauty of Yuichi who is in his early twenties. In what quickly becomes a gratuitous motif, the entire queer community of Japan begins to declare the beauty of Yuichi. Women, too, cannot resist him. It is his youth that is the secret to his beauty; he is beautiful because he is young. Seduced by an older aristocratic gentleman, Yuichi is lectured on his abstract status: “You don’t need a name. Indeed, beauty with a name doesn’t count at all…You, however, in your being are the animated universal name, ‘Young Man.’ Just imagine, a boy so beautiful he is the literal instantiation of the concept, the platonic form of beauty made flesh.”3 Although, given his promiscuity, perhaps platonic is the wrong word here.

In this same book where a not-so-subtle author stand in becomes the object of supreme desire, death lurks on every page. Yuichi is guided by Shunsuké, an elderly writer who sees in the boy’s beauty and homosexuality a chance to plot revenge on womenkind. The book is almost comically misogynistic at times. In the early pages, while Shunsuké’s less than justified hatred for half of the world’s population is being established, we are told of his third wife, “three years dead.” After running off with a lover she had committed suicide. Shunsuké knows why she took her life: “She feared the prospect of an ugly old age spent in his company.” Better to instantly perish than to slowly decay.

Throughout Forbidden Colors the elderly are rendered impotent. They are at times more self-possessed than the somewhat hapless Yuichi, but Yuichi’s beauty cripples all before him. They are powerless to resist. How can the same aesthetics that governs the immutable work of art govern the ever-aging body? The secret to this riddle is to live one’s life as a work of art. This means a certain ceasing to be once perfection has been achieved. The final act is the climax and then everything ends. This is the insight that compelled Mishima in his actions. Yet one cannot revise a life, and certainly not a final act. For all the pathos Mishima injects into his works, his own final act would be saturated with bathos.

Mishima’s demise is not as glorious as many believe. Morita did not succeed in successfully beheading Mishima and another member of their group, Hiroyasu Koga, had to complete the action. As a youthful Bailey Trela writes in his essay “Mishima’s Body”, this “didn’t exactly rectify the botching.” Mishima’s speech demanding the reinstatement of the Emperor was not heard by the soldiers whom he read it too, his voice failing to carry from the balcony and into the courtyard. Perhaps he intended this, the true spectacle being the TV cameras that caught his faint voice yelling into the abyss. The glory of grandiosity, the awe of the choregraphed is always a hair’s breadth from humiliation. The ballerina who tumbles off the stage enacts a literal fall from grace. Our dignity and poise is always a precarious affair.

There is a way in which art and life will always separate. The great sin of art is impotency, that it will fail to land its effects. One can rid their work of impotency, and this is what the great writers, including Mishima, do. One cannot rid one’s life of impotency. It does not matter how much wealth, power or success one builds, one cannot escape a rather sinister equality of human beings that Hobbes first identified with the state of nature. And one life is not enough time to succeed in every endeavour.

In many ways, Mishima’s final act seems true to his principles. Are we not, in discussing his act, proving his point? His final spectacle captivates us, he was willing to die for his belief in beauty. Where are such convictions now? He turned himself into a work of art and before he could decay, he froze the image of his beauty and his power into a single instant.

The word spectacular is oddly normative. It presupposes a certain amount of rapture from the presumed audience, those witless spectators. It is here, in the trick question of our attentiveness to Mishima’s closing act that I think we can understand the power of a film like Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters. Schrader’s keen insight is that cinema is the format in which Mishima can be rebuked. The first reason is this question of the spectacular, and the second is Mishima’s inability to grasp movement.

Despite his late career turn to acting, it is not clear Mishima understood the camera nor the moving-image. He never quite managed to overcome the unity of all dualisms. In this sense he was unsophisticated in his thinking. A good example of this comes from a comment by Japanese filmmaker Nagisa Ōshima. On Mishima’s early death he says, “I think he should have witnessed his old age, and his deterioration and his ugliness, for the sake of his art.” Mishima, having articulated a principle and committed to it, lost all sense of curiosity. Could this principle be pushed further, could deterioration be seen from within his idealized conception of beauty? In Sun and Steel Mishima will invoke the absolute often, but he seems unable to grasp that other arch Hegelian concept: the negative.

This plays out in his 1963 novel The Sailor Who Feel from Grace with the Sea. In it, Ryuji Tsukazaki is drawn away from his sailor’s life and into a life of domesticity with single mother Fusako. Fusako’s child is the amoral Noboru. At first Noboru is enamoured with Ryuji, but when Ryuji displays, again and again, a lack of strength and character Noboru finds himself disgusted with him. He brings a list of Ryuji’s sins to the leader of his gang, and they plan a gruesome end for Ryuji.

The novel’s value lies in a shock that is anticipated but never delivered. The book ends with Ryuji about to be knocked out by the gang, where presumably they will orchestrate their plan to execute him. Ryuji’s impotence is supposed to make us hate him, and his fall from potent sailor to oafish husband is meant to be a clear and irrefutable condemnation of bourgeois society. And yet, Ryuji displays a thoughtfulness and awareness that is a strength. Ryuji’s final transgression will be his refusal to beat Noboru. Fusako has discovered a peephole in Noboru’s room. It is clear he has spied on Ryuji and Fusako while they were intimate. For Fusako the shame is unbearable, she demands Ryuji punish Noboru. Noboru does not demand his own punishment, but he desires it, in so far as he desires to experience the strength and law of the father. While Mishima displays here an astute understanding of psychology—the demand to be punished, the desire for punishment and the innate respect of power—he refuses to see anything like strength in Ryuji’s calm and collected approach to the issue. We are meant to see delusion in Ryuji’s decision: “As he hurried to banish from his mind merely dutiful concern for this reticent, precocious, bothersome child, this boy whom he didn’t really love, Ryuji managed to convince himself that he was brimming with genuine fatherly affection.”4 And yet in the very display of this position and Mishima’s willingness to mock it, we are able to see it in its full force.

This is the power of the negative. Mishima, in order to valorise his vision of action, must show us examples of impotency. Mishima is a great novelist because his works often display this duality, and he encapsulates in his dramas these divisions. He is a poor thinker because he does not dwell on the meaning of these divisions and unities. If we find Mishima’s vision of life abhorrent, these characters we are supposed to find so repulsive display themselves as strong and wise. Did Mishima kill himself because he couldn’t bear to see himself feeble? Because he could not find beauty where there appeared to be none? What kind of strength allows such pride?

It should come as no surprise then that Mishima’s attempt to cement his beauty are undone in the artform of the cinema. It is Schrader’s film that works most ardently to undermine Mishima’s attempts at glory. In this form neglected intellectually by both Mishima and Sartre, Schrader stages a complex meditation about art and reality.

Schrader accepts Mishima’s union of life and art as set forth in Sun and Steel. The whole conceit of Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters is this separation. The film has two halves. One is biographical, shown in black and white. The other recreates scenes from Mishima’s novels, these appear in color, staged on sets more fitting the theatre than cinema. In these scenes the sense of artifice is exaggerated wherever possible.

This set up is already dialectical, setting up not just a combination of life and art, but a combination of cinema and literature. In literally staging scenes from Mishima’s novels, Schrader is introducing the literary into the cinematic. This is underscored by a single fascinating moment in the film. Schrader chooses scenes from The Temple of the Golden Pavilion and Runaway Horses. It was originally his intention to include scenes from Forbidden Colors as well, but Mishima’s wife denied Schrader the rights to the novel. Schrader turned instead to Kyoko’s House, a 1959 untranslated novel of four interconnected storylines. Schrader choose one of these storylines, of the actor Osamu, who ends up in a BDSM relationship with an older woman that culminates in a suicide pact.

The inclusion of Kyoko’s House means that Schrader’s film stages the first (and so far only) English translation of this Mishima text. In this the claim that Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters is literary is clarified: it is literally the only source for a translation of a literary work.

This is strange to consider, and it troubles the boundaries of literature and film. The problem of drawing any sharp line is that our concepts and definition are on the move. And in art, where what is at stake is the new, such lines are forever being erased. Schrader’s film is literature, in so far as it contains the first English translation of one of Mishima’s works. Schrader’s film is not literature insofar as it is a film and not a book. This kind of dialectical difficulty is alien to Mishima.

The self-consciously literary character of Schrader’s film is intentional, and forms part of its rebuke to Mishima. If, for Bazin, the plastic arts hold death at bay, for Mishima this is what literature does as well. In Sun and Steel he writes:

In literature, death is held in check yet at the same time used as a driving force; strength is devoted to the construction of empty fictions; life is held in reserve, blended to just the right degree with death, treated with preservatives, and lavished on the production of works of art that possess a weird eternal life.

The blending of these two forms in Schrader is a perverse denial of Mishima’s insights in Sun and Steel: he is pulling Mishima away from the perishing flower of action and condemning him to the immortal and artificial flower of literature.

Schrader’s film also functions as commentary on Mishima’s final act. Here Schrader is one step ahead of his subject. Mishima seemed not to consider that if he was to make of his life a work of art his final moments would be subject to criticism. What if he his final act was bad art? What if he, in his quest for glory, instead achieved humiliation? What if he, like our ballerina, tumbled off the stage ever so gracelessly? Here he stages the spectacle against the spectacular.

The simple trick of the film—black and white for reality, color for the literary—admits us onto Mishima’s own terrain. His final act is an act of art. Schrader admits this. Schrader then adopts, as is his right as filmmaker, the standpoint of the divine. He will play the part of fate.

At the end of Sun and Steel, Mishima describes a flight he takes in a F104 Jet Fighter. Schrader immortalizes this moment and turns it into the pivotal scene where Mishima’s fiction and his life converge. As the jet breaks through the clouds, everything is rendered in color. It is appropriate to depict the end of Sun and Steel this way, as the book itself sets the tone for Mishima’s final act more than anything else. The real revelation comes, however, earlier. Mishima, while training for his flight, suffers hypoxia in the flight simulator. It is the closest he has ever come to death. Having approached the limit, he is confident he wants to go beyond it:

Forty-one thousand feet, forty-two thousand feet, forty-three. ... I could feel death stuck fast to my lips. Soft, warm, octopus-like death, a vision of dark death, like some soft-bodied animal, such as my spirit had never even dreamed of. My brain had not forgotten that training would never kill me, yet this inorganic sport gave me a glimpse of the type of death that crowded about the earth outside. . .

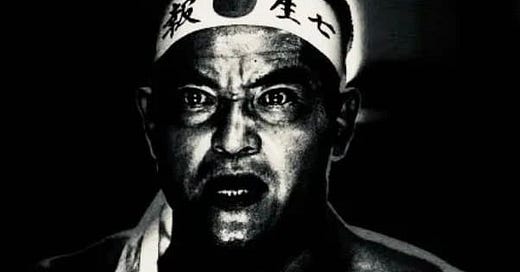

The confidence of Sun and Steel will be undermined by Schrader’s depiction of Mishima’s final moments. His Mishima, played by Ken Ogata, enters successfully the JGSDF HQ. Then the blunders begin. In Henry Miller’s book on Mishima, Reflections on the Death of Mishima, he claims that Mishima has no sense of the comedic. Without laughter our errors become humiliation. Mishima and his acquaintances struggle to subdue the military command. They block the entrance to the office which they have occupied, but everyone knows something is wrong. They restrain the commandant Kanetoshi Mashita in a cartoonish fashion, tying him to a chair. Mishima goes out onto the balcony, over the courtyard, delivers his speech, is booed by the bored cadets below. He goes back into office and prepares to commit seppuku. As he plunges the knife in, just as he envisioned when he wrote the closing lines of Runaway Horses, Schrader zooms in on his face. This is the final iconic moment of the film, one that adorns its posters and the cover of the soundtrack album. This is the moment the knife goes in, this is the moment Mishima dies, this is the moment Mishima achieves eternal beauty, this is the moment Mishima gets everything he wants. What is that look there on his face, what interpretive licence does Schrader take? We will never really know what Mishima’s final thoughts were, and Schrader is exploiting this fact. What might we make of Mishima’s ignoble end? What might he have made of it as it was happening? Schrader offers us his answer: the pained look across Mishima’s face is one of regret. Here Schrader plays a ploy against Mishima. In Sun and Steel Mishima had been looking for something beyond words and found it in the form of the body. Words were not to be trusted. They are corroding and useless. Yet Schrader himself is making a statement here. Perhaps Mishima does not have any last words, but then we will offer up in its place a last image. Cinema is a language also. Bazin, in a suggestive and all too brief footnote, claims that the proper predecessor to the camera is the death mask, which is also a kind of “automatic process.” The death mask and the camera alike aim to capture an impression. Schrader’s freeze frame is not just dramatic. It returns to the plastic art of the death mask. He models and creates Mishima’s last moment, giving one last impression of the ugly demise of a man so dedicated to beauty.

Mishima knew when to end a novel. In The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea and in Runaway Horses we need only the moment just before death actually arrives. This is not just because writing the moment of death is difficult for literature. It is because Mishima knows to stand back from these moments. It is good to leave something to the imagination. And yet there could also be another reason. That Mishima knew, somewhere, that all this violence and death was not as glorious and noble as he thought. Beauty has its other side, as does youth. Mishima didn’t understand movement, nor the negative. For if he did, he might have known that death is the only thing which is impervious to movement, that the negative becomes absolute in death. That instinct to avoid brutality which Mishima despised has its own insights. There are things in this world that are gruesome and nothing more, things which cannot be aestheticized into perfection.

Quotes from Sun and Steel are translated by John Bester.

Trranslated by Michael Gallagher.

Translated by Alfred H. Marks.

Translated by John Nathan.

Duncan Stuart is an Australian writer. His writings have appeared in Firmament, 3:AM Magazine, The Cleveland Review of Books, Jacobin, and Overland. He publishes a monthly substack, Exit Only, and can be found on Twitter @DuncanAStuart.

This is a great post, and I'm glad to have found something so original about Mishima. Thanks for writing this, Duncan!

The point you make about gracelessness is probably spot-on for Mishima's legacy in Japan -- most of the Japanese people I know, if they even know who he was, are clearly a little uncomfortable speaking about him. Whether this embarassment is a failure on his part, or their own failure to understand someone who lived so far outside the bounds of Japanese society (where suicide = shame, not pride), I'm still not sure, but reading your essay I'm thinking of the former. I remember one person, a retired high school Japanese teacher, telling me he found Mishima almost unreadable because of his overly Westernized style. He's a complicated figure.

If there's a moment in his life which seems to have stuck in the Japanese zeitgeist, it's probably his debate with the zenkyoto students in 1969. There was a hit Netflix documentary about it that came out a few years ago. His legacy is aesthetics (novels still sold anywhere you can get books here) and probably also political, but metaphysical/philosophical? Don't think he took off like he might have wanted.

Omg that last line 🥲