Magic Circles

On Rebecca West's The Return of the Soldier and David Lynch's Twin Peaks: The Return

“No man needs curing of his individual sickness; his universal malady is what he should look to.”

—Djuna Barnes, Nightwood

“All effort is a crime because every gesture is but a dead dream.”

—Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet

One of the more remarkable novels to address the impacts or symptoms of the First World War, rather than the direct experience of war itself, is The Return of the Soldier (1918) by Rebecca West: a kind of chamber drama devoted to the crises in subjectivity (to speak broadly) provoked by the war and its traumas, and especially by so-called “shell shock.”

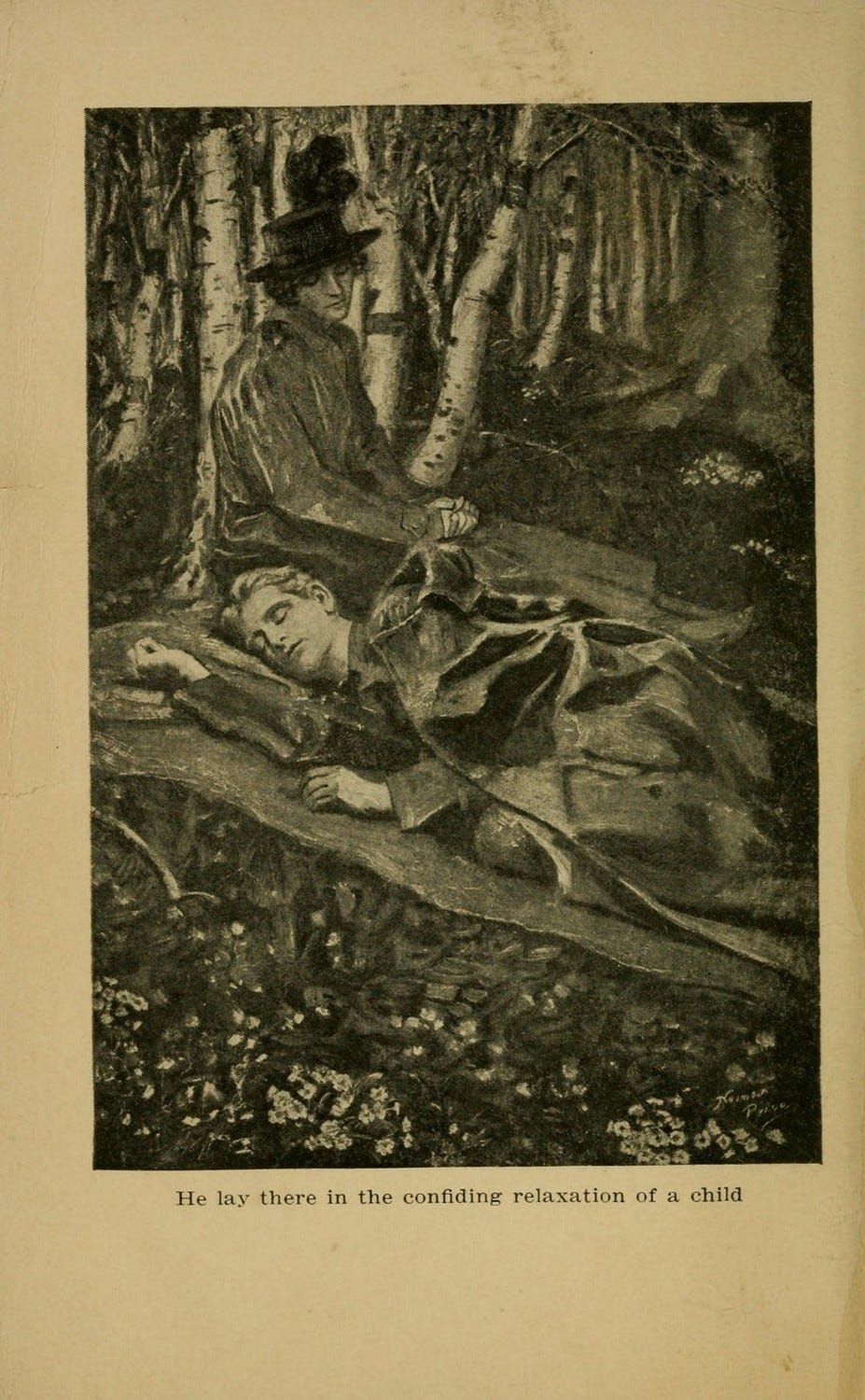

It’s a short novel, and its plot is deceptively straightforward. The narrator, Jenny, and her cousin-in-law Kitty, reside in the English country estate of Chris Baldry, Kitty’s husband who is fighting in France. Their idyllic waiting is disturbed by some news brought by Margaret, a lower-middle-class woman whose relative shabbiness becomes something of an obsession with the obviously jealous Jenny, who has been in love with Chris for years. But Margaret is not only distressing because she represents the growing and, to Jenny and Kitty’s eyes, squalid middle classes: she brings news that Chris has been injured in the war and is recovering from “shell shock.” It turns out that Margaret was notified, and not Kitty, because Chris has amnesia and has no memory of his wife, or indeed of the past fifteen years of his life. Trauma has returned Chris to a previous version of himself, a magically younger and happier man desperate to be reunited with his first love: Margaret. The tragedy—or if you prefer, the brutality—of the novel has to do with the reactions of the characters to Chris’ coping with, or through, trauma, and the extraordinarily ideological and prejudicial explanations our narrator, Jenny, furnishes to make herself feel better. It is, in brief, a novel about how the trauma called “shell shock” could be grotesquely misunderstood, and the cruelty of forcing a person always to be who they once were for us.

It’s worth lingering with the term “shell shock,” which ought to be understood as referring to much, if not all, of the multivalent traumas of WWI. According to the historian Jay Winter, it was “a specifically Anglo-Saxon representation not solely of damaged soldiers, but more generally of central facets of the war itself,” and it “helped people to conjure up the long-term effects of war service in a political culture unprepared to provide a special place for ex-soldiers and sailors.”1 In short, “shell shock” also encompasses the extent to which the war, its survivors, and their trauma could not be assimilated into normal society. Or as Tracey Loughran puts it: “Shell shock has become the emblematic disorder of the First World War”.2 She goes on to explain the contemporary meaning of the term: “it described a range of afflictions […] the experiences and symptoms of these men were bewilderingly diverse, and so were the explanations put forward for the disorder”. Accordingly, Loughran proposes a certain historical approach to “shell shock”: “in which wartime understandings of [the term] are foregrounded, and the term itself is viewed primarily as a diagnostic label […] ‘Shell shock’ would therefore be defined as the totality of its wartime meanings”. So, when we read representations of WWI trauma and its treatment, the problematic unity of “shell shock” as a label is rather urgently relevant. Its objective meaning is collective and capacious, and insufficient for understanding subjective trauma. But inevitably, the effort of intersubjective communication that a traumatized subject calls for is more difficult than simply applying the label “shell shock.”

This difficulty accounts, in part, for the inadequacy of authoritative responses to war trauma. As Loughran remarks: “empathetic imagining of a subject is not a replacement for empirical practice, but it is a prerequisite for asking questions with a human meaning.” Indeed, a practice of imagination that is both empathetic and critical is crucial for understanding “shell shock” and its literary representations. Historically, WWI calls for analytic scrutiny, and the individually traumatized subjects it produces call for empathetic imagining, but these dimensions or levels of thought are dialectically related: each is incomplete and subject to partial negation by the other, but if there is some final synthesis of reason and feeling available to us, I don’t know it.

Having granted “shell shock” some historicizing scrutiny, we can turn to Henri Bergson’s 1903 Introduction to Metaphysics, and his concept of intuition, in an attempt to empathize. What Bergson calls an “absolute movement” is to attempt to know a thing as it is for itself, as a subject: “I am attributing to the moving object an interior and, so to speak, states of mind; I also imply that I am in sympathy with those states, and that I insert myself in them by an effort of imagination.”3 As an example, he discusses the apprehension of a character in a novel by the reader: “Description, history and analysis leave me here in the relative. Coincidence with the person himself would alone give me the absolute.” Even that is a stretch, because no one is ever identical with a fictional character. And to only know a person’s trauma objectively, using external concepts, is to exclude their subjectivity from knowledge. As Bergson writes, “the concept generalizes at the same time as it abstracts”. So the term “shell shock,” multivalent and encompassing as it is, can “deform” trauma by making it “common to an infinity of things”. In Bergson’s terms, intuitive understanding can restore subjective experience to knowledge. If you prefer, you could think of this in negative terms as a preventative measure against dehumanization.

Subjective experience occurs in concrete spaces and conditions, and WWI bequeathed to the modern age a persistent image of dehumanizing spatial horror: the trench. But the horror extends far beyond the waste lands of Flanders, and what Adorno wrote of the Second World War is also true of WWI: “The idea that after this war life will continue ‘normally’ […] is idiotic. […] Normality is death.”4 Later in Minima Moralia he specifically addresses the valuation of objectivity over subjectivity:

Objective means the non-controversial aspect of things, their unquestioned impression, the façade made up of classified data, that is, the subjective; and they call subjective experience anything which breaches that façade, engages the specific experience of a matter, casts off all ready-made judgements and substitutes relatedness to the object for the majority consensus of those who do not even look at it, let alone think about it—that is, the objective.

By insistently inverting a commonplace division between what is “objective” and “subjective,” Adorno revaluates subjectivity within bad objectivity. The notion of “shell shock” is in Bergson’s terms a concept that “deforms,” and in Adorno’s words a “façade made up of classified data.” The domination of what is called objectivity amounts to a failure to recognize subjectivity as the foundation of any true objectivity: we are all subjects, and we forget this too easily. Subjective experience, and imaginative attempts to understand it, retain the critical potential to at least resist “majority consensus.” But that consensus tends to seek revenge.

In West’s The Return of the Soldier, individuated trauma becomes a site of contestation between objectivity and subjectivity. In Chris “shell shock” takes the form of apparently selective amnesia. He has forgotten the past 15 years of his life, including his marriage to Kitty, and is once again in love with Margaret, the woman he knew as a younger man. But he is not delusional, and though he eventually understands his situation, the objective facts do not dispel his subjective conviction—what we might want to call his actuality, as against the claims of objective “reality.” As Jenny claims: “I saw that deep down in him, not to be moved by any material proof, his spirit was incredulous”. When Chris is reunited with the wife he does not recognize, Jenny sees him struggling to navigate his subjective removal from his own marriage: “He looked round for some graciousness to make the scene less wounding, and stooped to kiss [Kitty]. But he could not.” He cannot return to objectivity because he no longer shares it with Kitty and Jenny; his subjective actuality, which no facts can fundamentally control, is out of sync with their reality, which belongs to the past no less than his. It is precisely through their denial of the war having changed Chris that Jenny and Kitty reveal their hypocrisy: they, too, are clinging to a memory and imposing it upon Chris.

The reactions of Kitty and Jenny to Chris’s new, and to them amnesiac and therefore “incomplete” subjectivity set the foundation for the imposition of a “cure” for his amnesia which will drag him back into deadly normality. Upon learning of his amnesia, Kitty callously remarks: “‘…there are bits of him we don’t know. Things may be awfully wrong. It’s all such a breach of trust. I resent it.’” His amnesia, enacted by trauma and understood as “shell shock,” is somehow a personal failing. Jenny, for her part, does come to a more sympathetic understanding of Chris’s condition:

It was our peculiar shame that he had rejected us when he had attained to something saner than sanity. His very loss of memory was a triumph over the limitations of language which prevent the mass of men from making explicit statements about their spiritual relationships. I felt, indeed, a cold intellectual pride in his refusal to remember his prosperous maturity […] for it showed him so much saner than the rest of us, who take life as it comes, loaded with the inessential and the irritating. […] But that did not make less agonizing this exclusion from his life. (emphasis added)

Jenny is clearly attempting to understand the way that Chris’s amnesia has produced a subjective reality from which he cannot return by force of will. He cannot make himself love Kitty, just as Jenny cannot help but love Chris and be pained by her exclusion. This emphasis on her own feelings—“shame,” “pride,” and agony—motivates Jenny’s final allegiance to objective truth, with disastrous consequences.

Gilbert Anderson, the last doctor brought to bear on Chris’s case, does not cure Chris so much as he enables Kitty, Jenny, and Margaret to collude in wrenching him out of happiness. As Jenny admits: “I had so great a need to throw off my mood of despair […] that I filled myself with a gasping, urgent faith in this new doctor”. But his presence is curiously disappointing, because he makes little effort to assert the primacy of normality: “‘It’s my profession to bring people from various outlying districts of the mind to the normal. There seems to be a general feeling it’s the place where they ought to be. Sometimes I don’t see the urgency myself.’” Margaret submits herself to the social demands made upon Chris’s normally recognized self, and says to Anderson: “‘You can’t cure him […] Make him happy, I mean. All you can do is make him ordinary.’” The objective normality that demands certain duties of Chris as a husband and soldier overrides the happiness Margaret has shared with him; she does not recognize, or acknowledge, that he truly has been happy with her. Immediately after Anderson admits that he sees no “urgency” in returning Chris to “the normal,” Margaret renders him irrelevant and assumes greater agency—but in service to normality. She claims that a strong memory would “bring [Chris] back,” and Anderson capitulates to her assurance: “The little man had lost in a moment his glib assurance, his knowingness about the pathways of the soul”. The doctor here has less authority than the family members and friends who appoint themselves the arbiters of Chris’s true self, and demand he return to his duty as husband and soldier. This suggests something rather unpleasant about the power of those who presumably love us most, as distinct from the institutional, Foucauldian power of doctors, etc.

In her final determination to “cure” Chris, Jenny unwittingly exhibits the “glib assurance” and “knowingness” she attributed to Anderson. She and Margaret decide that reminding Chris of the son he and Kitty lost will force his amnesia to break. Then, after seeing Kitty crying, Jenny makes a decisive apology for objective truth:

Why did her tears reveal to me what I had learned long ago, but had forgotten in my frenzied love, that there is a draught that we must drink or not be fully human? I knew that one must know the truth […] and celebrate communion with reality, or else walk for ever queer and small like a dwarf.

Then concluding soon after:

We had been utterly negligent of his future, blasphemously careless of the divine essential of his soul. For if we left him in his magic circle there would come a time when his delusion turned to a senile idiocy[…] He would not be quite a man.

As the critic Maren Linett argues, Jenny “elides the difference between psychiatric and intellectual disability, employing a common prejudice that views intellectual disability as the ‘lowest’ form of disability.”5 Her self-justification descends from high-minded talk of truth to offensive and bigoted claims about dignity, ability and delusion—none of which are truly relevant to Chris’s situation anyway. And as Adorno writes in Minima Moralia : “One need only […] note at what times the bourgeois talk of exaggeration, hysteria, folly, to know that the appeal to reason invariably occurs most promptly in apologies for unreason.” The terms have been confused: Jenny aligns patriarchy and a pointless war with reason, and happiness with embarrassing unreason. When Margaret, with Jenny’s approval, enacts Chris’s return, his subjective deformation is clear to Jenny: “He walked not loose-limbed as a boy, as he had done that very afternoon, but with the soldier’s hard tread upon the heel.” She implicitly acknowledges that after restoring him to his wife and home, their “cure” will send him back to the trenches. Thus, health and sanity have become inhuman criteria aligned with patriarchy, patriotism, and duty unto death.

Seen this way, such a relatively unfamiliar novel as The Return of the Soldier turns out to be uncannily reminiscent of Twin Peaks: The Return, perhaps the greatest cinematic achievement of the twenty-first century. I don’t wish to belabour the comparison. It suffices to note that, like Chris the soldier, Special Agent Dale Cooper returns in an all-but intractably changed mode of being, an entirely different subjectivity and consciousness, which is at first mistaken by many for stupidity or disability. And while West’s novel only hints that Jenny may regret “curing” Chris and returning him to the trenches, Lynch makes it amply clear that the abolition of Dougie Jones, and the astonishing and unnerving return of the “old” and supposedly familiar Agent Cooper, constitute the beginning of a calamitous fall—and not merely a fall from grace, but a fall from a second chance.

In what is, to my mind, the finest piece of writing about Twin Peaks, Lawrence Garcia claims:

…the Dougie Jones arc is nothing less than a complete absence of consciousness, and thus a complete failure of acknowledgement. There’s a certain pleasure in watching Dougie interact with characters major and minor over the course of the season, but it only goes so far. He is not awake to them—and we feel a lack.

Hence, the supreme release of Cooper emerging from his shock-induced coma in Part 16, which culminates with a series of acknowledgements. His awakening makes love possible—and with it, pain.

But I’m not entirely convinced by this point, and I have The Return of the Soldier to thank for that. Reading West’s novel has done more than prime me to notice its resemblance to the plot of The Return: it has opened up an alternative reading. If the enforced “return” of Chris is motivated by prejudice, isn’t it possible that the Dougie Jones arc is weaponizing our prejudices in favour of speech, motivation, acknowledgement—in other words, our addiction to characterology as would-be proof of humanity?

There is, of course, a precedent within Twin Peaks for Dougie: in the original TV series both Nadine Hurley and Ben Horne have some kind of mental break which results in new, or at least atavistic, identities; in each case they are eventually “cured” in one way or another, and every element of the series conspires to represent their more or less utopian “magic circles” as ridiculous, farcical, unreal, silly, and in short, absent of consciousness. It doesn’t seem to matter that the “new” Nadine releases Big Ed to be with Norma, making all three happier—or, for that matter, that while Ben Horne is playing with toy soldiers he can’t hurt anyone. Very oddly, it is precisely when it comes to the loaded concept of sanity that this supposedly revolutionary series threatens to be utterly conservative. But in light of this, and given the consensus that The Return re-writes all aspects of the original series, why shouldn’t we expect that the meaning of Dougie—as a new, better, not sane Cooper—is different from that of the antic dispositions in the depths of the show’s second season?

It isn’t really true that Dougie Jones has no consciousness and cannot acknowledge anyone or anything. Recall this line from The Return of the Soldier: “His very loss of memory was a triumph over the limitations of language which prevent the mass of men from making explicit statements about their spiritual relationships.” Arguably, Dougie simply acknowledges and loves differently, without providing vocal evidence for his thoughts, as would be conventional in most fiction (to say nothing of everyday life). I daresay that protecting and providing for one’s family, and then also for friends and strangers alike, is a form of loving; our desire for words that attest to recognition and affection, as if actions are insufficient, is not always a desire we should trust.

Must we condemn Dougie for failing to communicate, and must we prefer the tragic failure of Agent Cooper to the quasi-saintly successes of Dougie? Why should we conclude that the loving, if obscurely disabled Dougie is less true than the vengeful, questing Cooper? The transformation can hardly be read as a “supreme release” when it leads to the infamously bleak and harrowing conclusion of the entire Twin Peaks saga: not so much a scream into a void as a scream that voids. Upon “waking,” Cooper abandons Dougie’s family and promises that “he” will return soon, but The Return’s painstaking devotion to the phenomenology of nonidentity (recall that Diane first knew that she was encountering Cooper’s doppelganger when he kissed her) has taught us to distrust these “manufactured” doubles and replacements. Cooper may have replaced himself with yet another copy who will live out his days with Janey-E and Sonny Jim, but this has been bought with the sacrifice of the Dougie that we, and they, have come to know. What Cooper learns in the final moments of Twin Peaks is that there is a price to be paid for treating people like objects in this way: he has, as the much-repeated line from Crime and Punishment goes, destroyed and betrayed himself for nothing. And we were quite mistaken to have anticipated so eagerly and so impatiently the replacement of the reticent and unworldly Dougie Jones with the glib and falsely heroic Dale Cooper—this was our misreading, and our failure to acknowledge.

Recall The Elephant Man, and it becomes easier to see Lynch’s work as one long exploration of prejudice and its consequences: the dialectical relationship between normality and abnormality, between the identity-driven sameness of vague nostalgia for small-town American community, and the inevitable discovery of disturbing alterity underneath or within the same: a dialectic no narrative closure can halt or suspend, in part because, if viewed negatively, it introduces an infinite regress. If there is always the possibility of discovering a severed ear or a murdered girl, then evil can never be vanquished; and perhaps, as Lawrence Garcia argued, it is right to see this impossible, greedy desire for an end to the evil of pain and the pain of evil as the grand error Cooper demonstrates to us.

But if we deliberately view the Lynchian dialectic of normality and abnormality in a more positive or productive light—if, that is, we choose to try to understand before pretending that we know what we may, let alone should, acknowledge—then it becomes a process of revision and change, of expanded boundaries and delayed conflicts. Think of the memorable metaphysical motto of Twin Peaks:

Through the darkness of future past, a magician longs to see. One chants out, between two worlds: fire walk with me.

This can be read, fairly easily, as an apocalyptic, quasi-demonic call for a cataclysm that would sublimate reality itself. Situated outside time, longing to see through the darkness of our subjective limits, the magician calls for others to join him in a death-driven dance. But another way of translating “fire walk with me” would be to say that it is Lynch and Frost’s way of expressing the doctrine of mutually assured destruction.

So if we accept that for Lynch there are “two worlds” in conflict, perhaps we should prefer a little diplomacy. Perhaps the two worlds should try to communicate before rushing to acknowledge their differences. And while we may, with the Major, ultimately fear that love is not enough, that is no reason to stop trying.

Our two subjects here—coincidence and fantasy—are arguably the driving forces of the entire narrative saga that Twin Peaks unfolds. Coincidence is everywhere recuperated by narrativity as signals from “another place,” a different world or dimension—the error made by Cooper, as by us, is to assume that this world and its voices can be trusted. It has always seemed to me that the inhabitants of the Red Room, Laura included, are mocking Cooper. They serve him coffee that he cannot drink, they spoon-feed him cryptic clues and then admonish him for not solving mysteries quickly enough, and they send him on a quest doomed to failure. Is there some language barrier here, or are they toying with him for their own amusement?

And as for fantasy: not only do several characters temporarily live in altered states seemingly divorced from reality, but, moreover, the narrative begins to entertain disastrous, pop-philosophical notions of subjectivism: “We are like the dreamer who dreams and lives inside the dream. But who is the dreamer?”

There are two crucial observations to be made about this line delivered by Monica Bellucci in (of course) a dream reported by Gordon Cole, as played by David Lynch. First, the ancient fragment from the Upanishads, here taken out of context in Eliotic fashion, is very obviously a simile: the wisdom is in the observation that living is like dreaming, but not identical to it. This seems to make the second sentence nonsensical: it’s a category error, a misunderstanding of figurative language, a disastrous bit of literalism. Or perhaps it suggests to us the defining anxiety of the series, and maybe of Lynch’s work altogether: the terror of nonidentity, of suddenly and inescapably feeling alienated from oneself, of waking up as someone else, of not knowing what is real and what is a movie, of being trapped in someone else’s dream. But this is not mysterious at all. If we are alienated from our unconscious mind, that may be because our unconscious is political: my dreams are not entirely mine.

Jameson’s concept of the unconscious isn’t simply a handy tool for theoretically cutting Lynch’s work down to size, so to speak: it finally names the underlying mystery that motivates most of Lynch’s cinema. History is everywhere an absent cause in Lynch, until suddenly it isn’t absent. What is most radical about Part 8 of The Return isn’t that it forces experimental/surreal/abstract imagery upon a TV audience. It’s that it designates a true historical point of inflection as the original crime that produced all the chimeras and traumas of Twin Peaks. Laura Palmer, we learn, is not merely a victim of domestic abuse, nor was she merely killed by some demonic interdimensional spirit. She was a victim of the atomic bomb.

In this way The Return demonstrates that, far from being concerned merely with the local, internal problems of repressed violent desires in America, Lynch’s work is actually concerned with examining America as a place that pretends history only happens elsewhere: a country dreaming of war, and living inside that dream. It is telling, therefore, that someone as peaceful and as utopically benevolent as the “Dougie Jones” we come to know is assumed to be out of touch with reality, by characters as much as by us. We were wrong to want Agent Cooper—a supposed hero who never really saves anybody—to return. Again and again he fails to save the people—particularly the women—who define his life, and in the end his own repetition compulsion, his need to not have failed, is all that remains to define him. We should not admire his pathetic, unrealistic dreams of heroism, and I think that the real “magic circle” in Twin Peaks is Lynch’s FBI: a vision of that institution as a rarefied group of failures, in over their heads, out of touch with reality, unable to acknowledge the truth: the deaf leading the blind. And in the end, Lynch lets them go to their ruin.

Winter, Jay. “Shell-shock and the Cultural History of the Great War.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 35, no. 1, 2000, pp. 7-11.

Loughran, Tracey. “Shell Shock, Trauma, and the First World War: The Making of a Diagnosis and Its Histories.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, vol. 67, no. 1, 2012, pp. 94-119.

Bergson, Henri. An Introduction to Metaphysics. Translated by T. E. Hulme, 1912. Hackett, 1999.

Adorno, Theodor. Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life. Translated by E. F. N. Jephcott, 1964. Verso, 2005.

Linett, Maren. “Involuntary Cure: Rebecca West’s The Return of the Soldier.” Disability Studies Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 1, 2013. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v33i1.3468.

Ethan Gibson is a Canadian PhD student who writes about modernism and contemporary culture. You can find him on Substack and Twitter @ ethantgibson.

The idea of Cooper as a failed seer or magician began to really take twin peaks out of truisms or flat representations of ‘evil’, ‘good’ etc. It gives Lynch’s work the needed dimension that’s so often robbed of it, dispensing with his cynicism is just as much an error of doing the same with his deep sincerity. He feels and is able to capture Cooper’s failures of action, gestures and interpretation because of his understanding of each of these. This essay strengthened that direction of thought for me, and it helped me again feel, with new clarity, the whining pull of the mystery, and ultimate failure : ) good stuff

I'm always interested when, as you say, authors explore the harm done & cruelties inflicted by the people who love us. Very interesting, thank you!