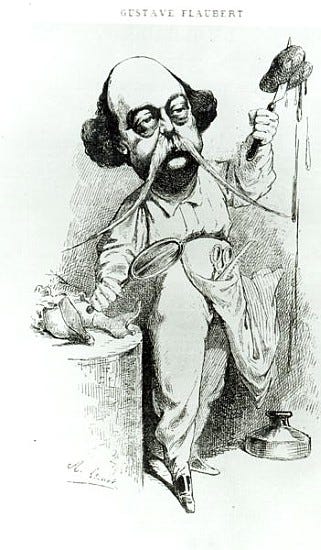

“An author in his book must be like God in the universe, present everywhere and visible nowhere.” So writes Gustave Flaubert in a letter to Louise Colet.1 This line appears so frequently in any writing about Flaubert that is has become a litany. Gather in front of the altar of literature and read from the divine letters of our dear Gustave: “AN AUTHOR IN HIS BOOK MUST BE LIKE GOD IN THE UNIVERSE, PRESENT EVERYWHERE AND VISIBLE NOWHERE.”

In Flaubert and Madame Bovary: A Double Portrait, Francis Steegmuller opens his biography in May 1845, where a “English-looking” Flaubert finds himself in the Palazzo Balbi-Senarega in Genoa, his gaze fixed upon a “repulsive canvas”: The Temptation of Saint Anthony by the elder Breughel. This religious painting springs in the young Flaubert an idea. He is certain of his powers as a writer, but he needs a subject to test them against and the dramatic, arduous ordeal of Saint Anthony—especially as depicted by the elder Breughel—was perfect.

In 1849, Flaubert called his two closest friends to his home in Croisset. Louis Bouilhet and Maxime Du Camp had been summoned to hear the completed manuscript of Flaubert’ s La Tentation de saint Antoine. In eight sessions of four hours each they listened as Flaubert read from his manuscript pages. When Flaubert finished reading, close to midnight, he cried, “Tell me frankly what you think!” It was Bouilhet, both more timid and more noble than Du Champ, who replied: “We think you should throw it into the fire, and never speak of it again.”

It is a Christian tradition to burn things. A practice so widespread has multiple justifications and motivations, but it became part of the Christian arsenal with the first inquisition against the Cathars. Heretics in the eyes of the Church, their beliefs included the necessity of burying the body whole, so that it could be resurrected on the final day of judgment. Thus, the flames aimed not only to purify but to curse as well. Bouilhet’s suggestion that Flaubert burn his manuscript perhaps revealed his hope that a work like Saint Antoine would not rise from Flaubert’s pen again.

There is another resonance here. The most famous burning of a heretic took place on the 30th of May in 1431. This was the execution of Joan of Arc who was burned at the stake for heresy (read: defying the English). Meticulous records of her trial survive, and they indicate clearly that no matter what she did the outcome was preordained by her judges. Joan was set ablaze in the Old Marketplace of the French Village of Rouen.

Rouen becomes, under the wrath of Flaubert’s pen, the site of another preordained execution. It is this town where Emma Bovary, the antiheroine of Madam Bovary, will take her own life, her tragic demise unfolding with all the certainty of a rigged trial.

Madam Bovary is the work Flaubert completed after his inquisitors had passed judgment on The Temptation of Saint Anthony. Here the religious resonances only multiply. For Madam Bovary is not merely a good book, it is a book that stands at the origins of a whole genre, realism. Scholars now debate this claim—we can push any origin back about 5 billion years it turns out—but it is Madam Bovary that raises painstaking detail into a compelling art and dismisses the last vestiges of romanticism from the novel. Flaubert’s scenes, which unfold continuously, never lapses into the romantic and magical vices displayed by Balzac, who is now considered merely a precursor to realism.

It is worth pausing for a moment here. Realism is a difficult genre to define. The first problem is that realism can mean both a painstaking depiction of reality and a realistic point of view. Realism is realistic in that it aims to mirror without distortion and that it seeks to take a clear-eyed view of things. Yet as a genre of art this cannot get past a certain level of irony. As Terry Eagleton points out in The Real Thing: Reflections on a Literary Form: “The Battle of Austerlitz really took place, but there can be no way of representing it which conveys every sword clash and scream of pain.” The problem goes beyond the impossibility of complete representation: there is no way out of artifice for art. The term itself presupposes this problem, the success of realism begins from the fact that it is not, in fact, the real thing. As Vladmir Nabokov puts it: “All fiction is fiction. All art is deception.”

Madam Bovary is a simple story. A doctor—Charles Bovary—gets hitched to the daughter of one his patients. This is Emma Bovary, the titular Madam Bovary. Her head is full of romantic ideas, but her marriage is unexciting, and Charles is a middling and pathetic figure. Madam Bovary wants passion, and she will find it in Rodolphe Boulanger and his airs of romantic nobility. After they consummate their affair in the woods, Emma can only feel the idling joy of one ruled by their desires: “I have a lover! A lover!” Yet for Rodolphe the affair is merely an affair, the romantic aspect is less important for him, and he distances himself for Emma. She becomes morose and unwell, causing her loyal and oblivious husband to despair. Soon another tryst emerges, this time with Léon Dupuis, a law clerk—they consummate their affair in the backseat of carriage, a coarse downgrade from the first transgression with Rodolphe. Léon also proves unable to commit to this wild affair. Heartbroken twice, and her debts mounting higher, Emma Bovary decides that if she cannot mould the world to her desires, she no longer desires a place in the world. She steals arsenic from the irksome town pharmacist Homais, ingests it, and dies a gruesome death. Charles, once again, despairs.

At first it may appear that this is the kind of story that could be told within 150 or 200 pages. Flaubert, however, spins entire paragraphs out of a single object. This commitment to weighing almost every detail swells the book to over 400 pages. Yet the book does not suffer for this, its style preserves the action. As Flaubert puts it in a letter: “I maintain that images are action.” Only style can prevent this dictum from producing bathos.

This hyper attention to detail begins on the second page. Here is how Flaubert describes the cap a young Charles Bovary wears on his first day at a new school:2

It was one of those composite types of headdress, which hints at bearskin, chapka, round hat, otter skin hat and cotton bonnet; one of those sorry contraptions whose dumb ugliness has certain expressive depths, like the face of an imbecile. Egg-shaped and bulging with whalebone, it began with three circular sausage shapes; the came alternate lozenges of velvet and rabbit skin separated from each other by a red band, followed by a sort of bag ending in a pasteboard polygon covered with a complicated piece of braid, and from which hung, at the end of a long and too-slender string, a little crisscross of gold thread by way of a tassel. It was brand new; the peak shone.

It doesn’t take much interpretive skill to see in the hideous and pathetic hat a hideous and pathetic Charles Bovary. There is a sense in which this level of detail is not necessary. And yet not a word has been wasted. The passage does not stilt or stutter.

This level of detail, as well as the quotidian subject matter, is at the heart of claims that Flaubert is a realist. There are those who are wary of calling Flaubert a realist, they have a good case: Flaubert himself would never write another novel quite like Madam Bovary and he himself was wary of the term. However, this position tends to leave only one other appealing option (unless you opt out of classifying authors altogether).

Those who are sceptical of Flaubert’s status as a realist opt to call him a naturalist. The distinction is subtle. Precisely because Flaubert is unsentimental, and he attempts to create a detached, objective prose, he appears as if he adheres to the core idea in naturalism: the world is explicable in scientific or natural terms. Just as with realism Flaubert sits awkwardly ahead of Balzac, here he dangles uncomfortably away from Emile Zola, who is the French exemplary of naturalism. It is Zola who declares, “I am simply an observer who states facts.” In the overwrought details of Madam Bovary one suspects it is this principle at play, even though it would not be uttered until 23 years after Flaubert published his masterpiece.

If one reads on from the simple Zola quote above—it appears in his essay “Naturalism on the Stage”—one will read this: “One thing is certain, I have no new religion in my pocket. I reveal nothing, for the simple reason that I do not believe in revelation; I invent nothing…” The scientific style of Zola reflects a particular scientific belief—naturalism as literary genre and scientific method cannot be disentangled. Yet while it is appropriate to call Flaubert’s prose scientific and Madam Bovary unsentimental and harsh, Flaubert himself was anything but a naturalist.

We might suppose that the attempt to build an accurate reconstruction of the world is a scientific endeavour. There goes Darwin on the HMS Beagle to makes notes and drawings of tortoises hitherto unknown. But there is a crucial difference between the writer and the scientist, and this distinction escapes Zola. Zola’s “I invented nothing” is an attempt to disavow the creative act from the novelist’s practice. Flaubert’s own reflections on art could not be further from this. In a letter to his lover Louise Colet, dated December 9, 1852, he wrote:

The author’s comments [in Uncle Tom’s Cabin] irritated me continually. Does one have to make observations about slavery? Depict it: that’s enough. That is what has always seemed powerful to me in Le Dernier jour d’un condamné [The Last Day of a Condemned Man, a novel by Victor Hugo]. No observations concerning the death penalty. Look at The Merchant of Venice and see whether anyone declaims against usury. But the dramatic form has that virtue—of eliminating the author. Balzac was not free of this defect: he is legitimist, Catholic, aristocrat. An author in his book must be like God in the universe, present everywhere and visible nowhere. Art being a second Nature, the creator of that Nature must behave similarly. In all its atoms, in all its aspects, let there be sensed a hidden, infinite impassivity. The effect for the spectator must be a kind of amazement. “How is all that done?” one must ask; and one must be overwhelmed without knowing why. Greek art followed that principle, and to achieve its effects quickly it chose characters in exceptional social conditions—kings, gods, demigods. You were not encouraged to identify with the dramatis personae: the divine was the dramatist’s goal.

This passage contains the most notorious of Flaubert’s epistolary pronouncements, with which I opened this essay: “an author in his book must be like God in the universe, present everywhere and visible nowhere.” Flaubert will consistently, in his letters, align his work and the creative act not with science, but with religion. In an essay on Flaubert and Madam Bovary, J.M. Coetzee writes “writing is no longer a matter of finding words to represent a given, pre-existing world. One the contrary, writing brings a world into being.”

Zola’s confusion is understandable. Zola believes that Flaubert has set out to describe a world: Flaubert’s world of provincial, bourgeois France. Indeed, did Flaubert not spend most of his life in Croisset, near Rouen? Flaubert then seems like the naturalist, the journalist, the observer. The causality is the wrong way around; “everything one invents is true” Flaubert says in another letter. Flaubert is not the observer but the architect. Madam Bovary is not a report, but a blueprint and Flaubert is not the scientist but God himself.

This is underscored by a peculiar moment in Madam Bovary. Emma has been abandoned by her first lover. He has begun to find her frivolous, overly romantic. Emma is caught in the fissure that splits all adulterers in two: the satisfaction of desire will always bear the mark of the immature. Self-control and prudishness may be oppressive and repressive—a great legacy of the Church, to press desire into a corner much darker and more sinister than anything in front of it—but it is also at times a mark of maturity and discipline. Rodolphe has broken off relations with Emma after he has realised that she possesses desire without restraint. Her devastation is described like so: “sorrow rushed into her hollow soul with gentle ululations such as the winter and wind makes in abandoned mansions.” Nabokov writes on this passage that “this is the way Emma would have described her own sorrow if she had artistic genius.” It is Flaubert who knows his characters better than themselves, who can extend and enhance their qualities.

It depends on which doctrine and mystic you wish to invoke, but it is not a foreign idea in Christian theology to note that all that makes us good, that makes us better, is a sign of the divine within. In so far as we are scarred by the infinite—in our desires and our capacity for growth and change—we are marked with divinity. Such an argument can be found in the writings of Swiss mystic Maurice Zundel, but it is also present when Flaubert leans in to extend the grace of one of his characters, to show that somewhere in his creative powers is exactly what they are missing.

When it comes to this question of defining Flaubert as a realist or naturalist, it is perhaps best to understand his work as a kind of mystic realism. All this identifies is the difficulty of a position like Zola’s, that the creative act is something a little more than the natural world. The novel is not a field report. The act of creation is a divine one. Every major and minor religion has a creation myth. This simple fact has a consequence: the creative act has a mystical resonance. We might not have ascended divinity when we approach the new, but we are partaking in it. This is especially so when what is being created institutes the formation of a rupture, of new style or form of artistic creation.

This element of creation and of newness was Flaubert’s explicit goal. In another letter he writes, “I believe the novel has only just been born, it’s waiting for its Homer.” Flaubert sees himself as this Homer, as one codifying and invigorating the new. He is explicit about at least one aspect of this in a letter to Louise Colet dated April 24, 1852:

I envision a style: a style that would be beautiful, that someone will invent some day, ten years or ten centuries from now, one that would be rhythmic as verse, precise as the language of the sciences, undulant, deep-voiced as a cello, tipped with a flame: a style that would pierce your idea like a dagger, and on which your thought would sail easily ahead over a smooth surface, like a skiff before a good tail wind. Prose was born yesterday: you have to keep that in mind. Verse is the form par excellence of ancient literatures. All possible prosodic variations have been discovered; but that is far from being the case with prose.

If we are to invoke the term naturalism by identifying it with a weltanschauung (worldview), then perhaps we can see the dissatisfaction at calling Flaubert a realist. Both realism and naturalism are false indicators of Flaubert’s views. And if we understand what divides Zola from Flaubert as mysticism regarding art then Flaubert’s designation as a mystic realist comes into focus. Flaubert was clear eyed and cynical about every part of human life except art. The world is a cruel and unforgiving place, but at least it makes for good literature.

Flaubert’s own awareness of his mystical impulses puts him one step ahead of so many of his critics and followers, who would associate him with an increasingly secularized world. Well, all but one. It is Nabokov, with his characteristic insight, who sees the hint of divinity in Flaubert’s work. Certainly, it is there in Madam Bovary itself, a great act of creation. Yet it is also there in what can only be described as an accidental touch of grace. It is Charles Bovary, hapless cuckold, who is touched with divinity. His love is innocent, but also absolute and pure. Nabokov has his finger on the pulse: “So here is the pleasing paradox of Flaubert’s fairy tale: the dullest and most inept person in the book is the only one who is redeemed by a divine something in the all-powerful, forgiving, and unswerving love that he bears Emma, alive or dead.”

This is a strange way to speak of Charles Bovary, a character Flaubert himself saw as rather pathetic. God’s creatures can turn on him, and often do so with glee. It is perhaps this hint of “divine something” that Jean Améry identifies when he sets out to write his novel Charles Bovary, A Country Doctor: Portrait of a Simple Man.3 Here Améry attempts absolution on Charles Bovary. We must recall that there is an inherent concern of transcendence for Flaubert. With the idle useless thoughts of the bourgeoisie in his crosshairs, Flaubert does hope to escape from the current malaise of French society. In this respect Flaubert, in more than just his immediate artistic sensibilities, has his eyes aimed toward heaven.

Améry’s tome of absolution keeps its mind in hell. Flaubert sought to overturn every bourgeois platitude and manner and with sinister glee spun his tale. Améry picks up the corpse of Charles Bovary, withered with despair and makes of him a saint. Yet this reversal is only possible in the explicit aftermath of the Holocaust. After God has abandoned earth, perhaps it is not so terrible to suffer the vapidity of a Homais.

Flaubert’s attempts to make a fool out of Charles Bovary backfire. It is the legacy of the martyr to endure humiliation after humiliation, and to return to the site of suffering unwavering in his devotion. Thus, Saint Sebastian—a favourite of Yukio Mishima (more on him next month!)—shot through with arrows miraculously survives. This is not the moment of his martyrdom. That comes latter, as he returns to proselytizing and is bludgeoned to death.

Charles not only endures, but he also blindly sets up Emma for her affairs. Améry constructs a more interesting, more tragic and more divine country doctor. A Charles aware of the affairs; “I gave it my unholiest blessing, against morals, religion and reason, so the fatalité of her beauty could be fulfilled”. It will be Charles in the end who tends to Emma’s corpse, who deals with the mess she has left, who feels bereft. Léon and Rodolphe would never be capable of such acts of devotion. There is a gap between love and love-making that is never quite bridgeable. In fact, pure desire cannot be realised at all, and as many learn early in adulthood, it has its best chance of being realised away from those who bear you affection. In this world, there is something more than mere flesh.

Charles Bovary, Country Doctor is a broadside against Flaubert, but it engages in the mystical elements of the text. There is the obvious sense in which this is true: Améry focuses his efforts on the one character who might be called divine. It is true, however, in another sense as well. Just as we have seen Flaubert’s extension of grace to his characters, by accident or not, we can read Améry’s novel as an extended act of grace. The creation of all things ensures damnation and redemption alike.

Letters throughout this essay taken from the reissue of The Letters of Gustave Flaubert edited and translated by Francis Steegmuller, published by NYRB Classics.

Quotes from Madam Bovary taken from Adam Thorpe’s translation published by Modern Library.

Recently reissued, also by NYRB Classics.