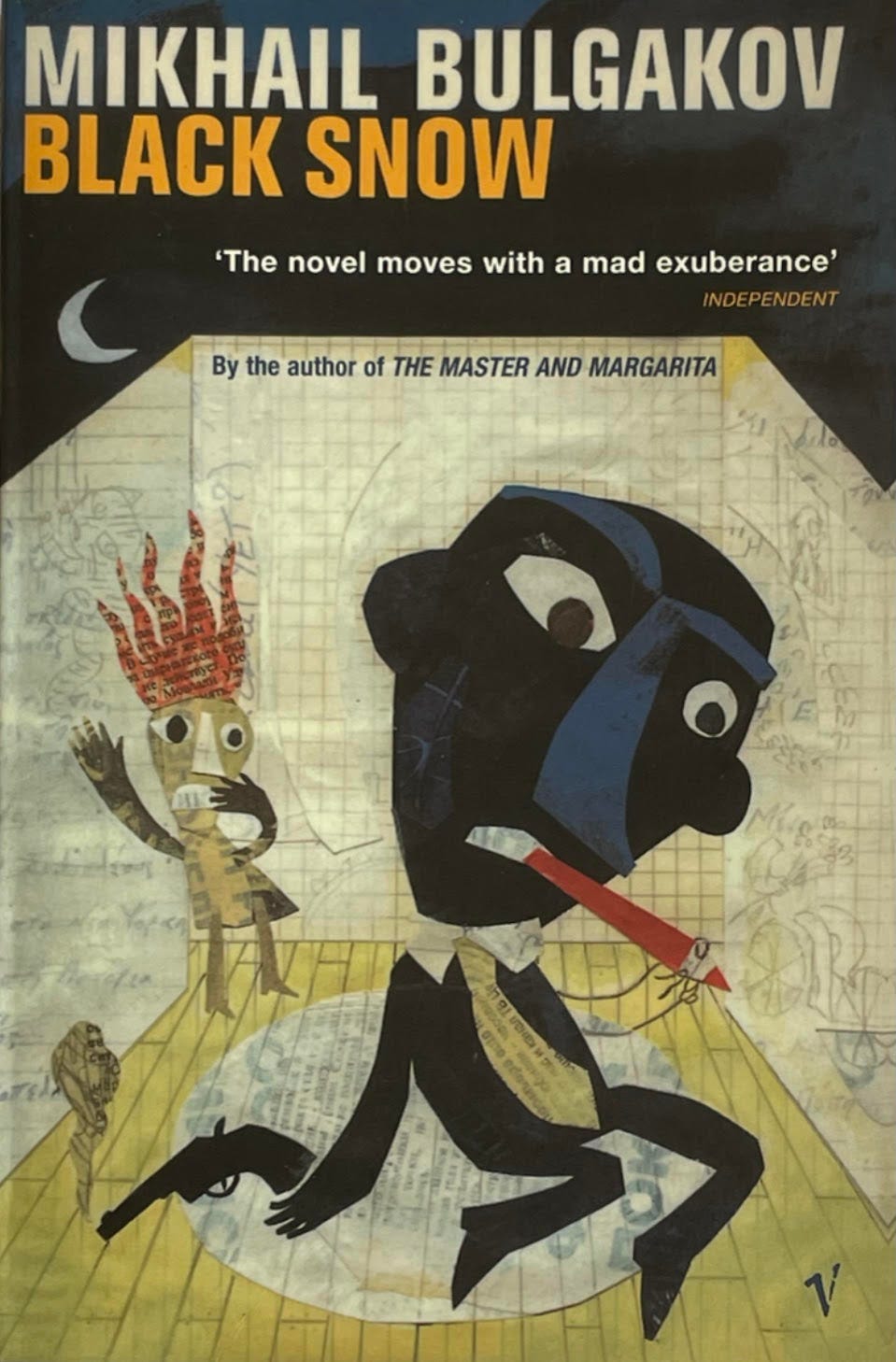

Black Snow (translated by Michael Glenny) is published by Melville House.

In the 1960s, Mikhail Bulgakov’s widow Yelena sent a grateful letter to the then-Literary Director of the Moscow Art Theatre, Pavel Markov. Markov had written an article on the reader’s interpretations of Black Snow, Bulgakov’s novel based on his time with the theatre. Popularly regarded as comic, Markov challenged this, declaring “the reader’s approach to Black Snow said something about his intellectual level”1. Bulgakov’s experience had been fraught to say the least, with in-house intrigues and petty drama between factions of the co-founders Konstantin Sergeyevich Stanislavsky and Vladimir Ivanovich Nemirovich-Danchenko, not to mention the more serious and personal problems with lack of autonomy in regard to his writing, censorship, and play direction. Michael Glenny, the translator of the 1986 Vintage edition, even goes so far to state in his introduction that Black Snow could be regarded as a revenge novel.2

Whether one agrees or not with Markov’s assessment of the comprehension of the reader, especially at a time when Black Snow’s readership has for some time been global rather than local, a phrase Yelena Bulgakova writes in her response strikes me as the heart of the matter if the reader is also an artist—more specifically, a writer: “It is about the same tragic theme to which Bulgakov constantly returned: the artist in conflict.”3 It is true that to a reader new to the book, or Bulgakov generally, that it is not necessary to know the history of the author. However, for most of his books it serves to enhance by giving personal insights and new perspectives as to the reading itself. That said, for the benefit of readers new to him, I will not go too much into the real life aspects of Black Snow here. Looking at the story mainly from the viewpoint of the conflicted artist provides both comedy and desperation in a way that writers are uncomfortably familiar with, and proves that nothing really changes in the creative world.

Bulgakov’s protagonist Maxudov, proof-reader at a little magazine, writes a novel in his spare time. A purely naïve endeavour as a result of a nightmare, he spends a winter in poverty-struck solitude working on it. Come spring, he makes his first mistake and steps into a larger writing world by having a reading. Everyone comes for the alcohol and food while gleefully telling him how awful it is. Not without promise, but still bad (the writer-as-reader will no doubt hear the current damning phrase, “while there is much to admire…” in their head). What follows is a frenzy of editing, more readings, more failures. Maxudov is hooked by the despair-cycle of writing, thinking his work awful, yet pinning every conceivable hope to it. He edits to attempt to avoid the official censor, he gets rejected. This goes on until one day, seeing no end, he decides to take his own life. Stealing a gun from a friend, he sits in his darkened (the sole lightbulb has burned out) room during a thunderstorm and listens to a neighbour playing a recording of Faust. At the eleventh hour, on the verge of going through with it, the devil appears.

Unlike in The Master and Margarita, considered by most his masterpiece, Bulgakov’s use of mysticism and sleight-of-hand does not take the form of actual demons and magic, but something more along the lines of what the late magician and writer Ricky Jay referred to in dice as “virtually synonymous with cheating”4. The editor Rudolfi’s dramatic appearance causes Maxudov to briefly believe he is being visited by Mephistopheles in a frantic scene Bulgakov loads with multiple literary nods. The demon at the service of Lucifer is there to provide both Faust’s bargain—tailored to writers—and light, by practical means of a lightbulb. Thoughts of suicide vanquished, Maxudov is persuaded by Rudolfi to sell his manuscript to The Motherland, “the only privately-owned magazine in Russia”. The power of the demon-editor is such that he tells Maxudov precisely what and where to cut to avoid the censor: here again Bulgakov plays with the mystic, as words cut include “apocalypse,” “archangels,” and “devils”. Real life later collides with this brief magical interlude when Rudolfi disappears (to America, where the would-be writers are plentiful), leaving Maxudov a stack of ubiquitous contributor copies and trying to get the rest of his promised payment.

Faust-Maxudov’s bargain plays out precisely the way any writer’s would: published in a prestigious magazine, he goes to literary parties, is praised to his face and spoken ill of behind it. He learns the ins and outs of the scene, which include everyone using their contemporaries’ lives as material. Turning down an inexplicable offer to use someone’s provincial brother-in-law who is a wealth of stories, he later purchases a book by a fellow author only to discover they utilised them instead. Frustrated and broke, he returns to the job he quit: “I told the manager I had been writing a novel. He was not impressed.” But it is precisely at this point that his bargain starts to reward him again. Contacted by the famous Independent Theatre who want to turn his book into a play, he is immediately thrown into waters where he finds soon enough that sharks would be preferable to theatre people. At one point he is given a contract to sign where almost every clause starts with “The Author shall not”. Only one differs, and it ominously states, “The Author must”. What the author must do, it conspires, is turn his work inside out according to the whims of the heads of the Independent.

It is worth noting that while superficially Black Snow does indeed come across as an intensely funny story of one writer’s hellish foray into the creative world, at no point, magical embellishments aside, does it feel unrealistic. Bulgakov’s skill in writing that most dangerous of genres, autobiographical fiction—especially based on terrible personal events—is such that the farcical, even at its most absurd, translates into what a lot of writers would merely see as the familiar. The trial of getting paid (and the full amount) is a running theme, as is being told to edit work beyond recognition, thinly veiling dramas to turn into dramas of a different sort, trying to get something for nothing, and taking sides in order to survive. When talking to Markov, writer and critic Anatoly Smeliansky was shown a manuscript of Black Snow which revealed Bulgakov’s corresponding of character to real-life person5; this is absent in my copy and I cannot help but feel including it would compel more readers to find out about the actual drama behind the book.

Bulgakov takes the two plot devices from the beginning of the story—Faust and the gun—and works them into Maxudov’s play: in doing so he creates a deliberate, labyrinthine headache. The reader becomes more lost in attempting to separate the various threads of character-fantasy and character-reality (and where applicable, Bulgakov’s experience), mimicking Maxudov’s increasingly fractured state of mind. The gun, after a first reading, could be seen as a reference to Chekhov’s maxim, and can be interpreted as such, but a darker interpretation more reflective of Bulgakov’s time at the Moscow Art Theatre would be to see the gun’s presence and reappearance as the ever-present shadows of Stanislavsky and Stalin, tyranny being something of a moveable feast in and out of the book. The former, one of the co-founders of the theatre and its director was detested by Bulgakov, and the latter, needing no introduction, was responsible for lifting the ban placed on The White Guard, the play based on his book The Days of the Turbins,6 putting Bulgakov in the constricting position of being admired by the most dangerous man in Russia.7 In that light, the gun looms over the text and Rudolfi’s lightbulb shows the glaring reality of creative compromise.

By the end, we are left laughing but hollowed, Yelena Bulgakova’s words about the artist in conflict discordant and echoing alongside the clauses of the fictional contract: the author shall not, the author must. What can the author do to preserve their sanity, if not their life when creating? The answer means paradoxically never straying beyond Maxudov’s innocent dream state. After that, Bulgakov implies, it is only devils all the way down.

Smeliansky Anatoly, Is Comrade Bulgakov Dead?, Trans. Arch Tait (London: Methuen, 1993), 328.

Bulgakov, Mikhail, Black Snow, Trans. Michael Glenny (London: Vintage, 2003), 11.

Smeliansky, Is Comrade Bulgakov Dead?, 329.

Jay, Ricky, Dice: Deception, Fate, and Rotten Luck (New York: The Quantuck Lane Press, 2003), 24.

Smeliansky, Is Comrade Bulgakov Dead?, 328.

Bulgakov, Mikhail, Black Snow, 6.

In 2011, the National Theatre in London ran a production of Collaborators, a nightmarish satire about Bulgakov and Stalin working together on a play which featured Stalin regularly ringing up Bulgakov to share his ‘wonderful’ ideas.

Tomoé Hill’s writing has been featured in places such as Vestoj, MAP Magazine, Socrates on the Beach, Exacting Clam, The London Magazine, and Music & Literature, as well as the anthologies We’ll Never Have Paris (Repeater Books) and Azimuth (Sonic Art Research Unit at Oxford Brookes University). Her book Songs for Olympia, a response to The Ribbon at Olympia’s Throat by Michel Leiris will be published in 2023 from Sagging Meniscus Press. Twitter @CuriosoTheGreat.