They all love to talk about Dante—well, not all of them, really, but enough to constitute a trend. When you pull up a scholarly text on Samuel Beckett’s Quadrat 1+2, his limit-pushing 1981 teleplay “for four players, light and percussion”, it will more likely than not mention, with the slightly-smug eagerness of a child sharing a fact they believe to be, maybe, just a bit naughty, that said players, who do nothing but move along the edges and through the middle of a square of empty stage, only ever turn to the left—just like (and here is the part where your eyebrows are supposed to rise a hair in measured appreciation of the Implications so deftly implied) the damned in Dante’s Inferno. It is a common enough recurrence to inspire Graley Herren to drolly quip, following a brief review of the extant Quadrat literature, “If constantly turning to the left were all it took to constitute a Dantean allusion, then the entire NASCAR circuit would qualify as one big Inferno.”1

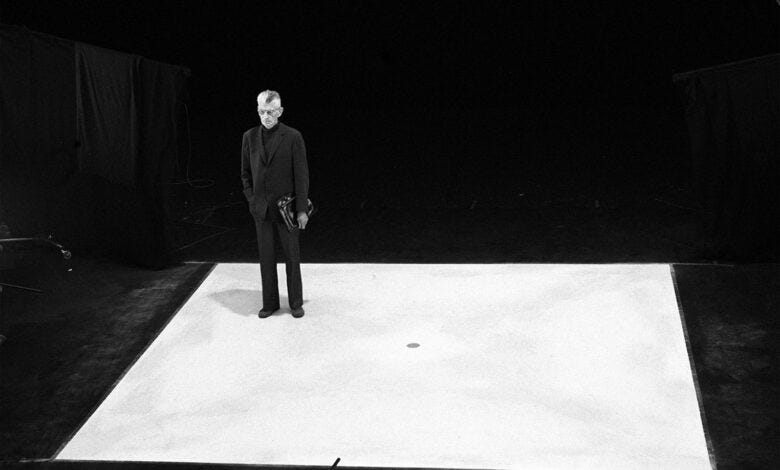

Setting aside the question of whether or not this is really such a ridiculous idea, let me say that there is, certainly, some sort of significance to the fact that it is this particular comparison (to Dante, not NASCAR) which crops up with such frequency in the work’s reception. We’ll come back to this, but let’s first establish, as everyone else does, the preliminaries necessary for any extended discussion of the work: Quadrat 1+2 is a teleplay (or telemime, if we wish to be especially precise) in two parts, produced in Stuttgart for the West German TV station SDR in 1981. Its first part, referred to in the script as Quad I, features four performers, or “players”, each wearing a sort of hooded gown of a different color (1 in white, 2 in yellow, 3 in blue, and 4 in red). The set is a dimly lit square of bare stage, surrounded by darkness. It’s shot from a single, raised perspective, somewhat like a tennis match. Each player has an assigned corner of the square, from which they enter and exit its matrix, and an associated percussion instrument, which is played, off-screen, only when they are within the square. Between entering and exiting, the players complete a “course” which traverses all four sides of the square once, and the middle diagonals twice, once from each direction. These entries and exits are sequenced such that all players are able to complete their course without colliding with another, even when all four are traversing simultaneously. Essential to this choreographic feat is the designation of the central point of the square as a “danger zone” which the players must sidestep (always to their left, of course), rather than pass directly through. This sequence is repeated four times.

As originally scripted, this was the entirety of the teleplay, but late in the process, after his producer at SDR, a Dr. Reinhart Müller-Freienfels, “told him how impressive the piece looked in black-and-white on the monochrome monitor in the production box”,2 Beckett was inspired to add a monochromatic “variation”, Quad II, in which the players are dressed uniformly in white, move more slowly, and are accompanied only by the steady tick of a metronome. They perform the same sequence as before, but only once this time. Beckett conceived of this second sequence as taking place “ten thousand years later”. This last detail is sometimes mentioned by scholars, and sometimes not. When it is, they rarely seem to know what to do with it, and the fact is allowed to pass more or less uncommented-upon.

This is, more or less, the basic description of the piece you’ll generally encounter in the literature—however, it omits a notable detail: in the teleplay as broadcast, neither of the two parts begin, as it were, at the beginning. There are the silent, somber opening credits, and then, without warning, we’re dropped into the action mid-stream, with 1 and 2 (i.e., the white and yellow-clad players) already mid-way across the square, respective percussives hammering away. This is not accidental: both cut out in a similar fashion, with a player still “on the course” as it were. The consequence of this is that we cannot, on the evidence of the text, treat either of these parts as self-contained wholes; we cannot say when they begin or end—or if they are even separate events. There’s a fairly straightforward explanation for the lack of attention given to this, in my opinion, rather important detail: despite his film and television work, Beckett is, primarily, a literary figure, and his work is written about, primarily, by literary scholars, who are going to be inclined to treat the script, not its screen realization, as the primary text—and on the page there is simply a list of straightforward, unambiguous instructions. Nothing about when to cut. In my research for this essay, I even encountered a journal article which treated the work as though it were simply a theatrical piece, as though it were of no importance at all that it was conceived and realized for a single camera eye, and not a crowd of living ones.

But, of course, what a work actually is, and not merely what it resembles, is a matter of some consequence. A reading of Quadrat based solely upon its script is one in which it ceases to be a dramatic work at all: there are no characters, no conflict, just a set of very simple instructions. I don’t think it would be a waste of time to undertake such a reading, by any means—the script’s resemblance to a sort of crude computer program is something very much worth unpacking—but the thing about a teleplay, any teleplay, is that the script is very much a subordinate document. Unlike a play written for the stage, the production of a teleplay results in a single, specific video-text that constitutes an absolutely authoritative realization (especially, as is the case here, when the writer also handles directorial duties), and it is upon its specificity that any serious interpretation must be based. As Enoch Brater argues, in an essay discussing the two Quads alongside Beckett’s other late mime Nacht und Traüme, “In these wordless plays there is no real script, only the pretext of one. There is, however, a performance, one, moreover, which is meant to be regularized and fixed forever on videotape. The performance we see on television is the text, for in Quad I and II the verbal element has been ultimately suppressed”.3 If we accept this, then we must also acknowledge that, as a text, Quadrat 1+2 begins and ends in midstream. Its narrative (and this is what it is; a prerecorded television broadcast, being a linear, determinate sequence of photographic images, is always a narrative) has no definite borders.

It’s this particular ambiguity, this openness which is not present in the precise, mathematical schema of the script, which is the key to the mystery of Quadrat 1+2, the thing which sets it apart as uniquely fascinating. Beckett’s late work, like the late work of most great artists, is uniformly rewarding, but it is the product of a process of reduction (in the same sense as one “reduces” a substance by boiling it away) so well-developed that, by now, it almost exclusively generates closed systems, monads, strange, barren little miniature worlds which exist, one suspects, somewhere outside of “time” and “space” as we would understand it. For example, in Ohio Impromptu, a piece for the stage completed shortly before Quadrat 1+2, in which a Reader reads to a Listener the last few pages of a book describing a life finally winding down into nothing but the act of reading, and then nothing at all, it is very difficult to imagine anything happening after the lights go down besides the scene “resetting” like a record on a turntable, or the darkness simply continuing, unbroken, forever. This is a situation which has already been exhausted, which is already in its terminal state, beginning after its own meagre history has ended (there is an untranslated Deleuze essay, fittingly titled “L’épuisé”, in which he argues exhaustion is the “goal” of Beckett’s late dramas and teleplays). It can either begin again or cease to exist—there is no “after” anymore, no future. But there is an “after” in Quadrat 1+2. By many measures it is the most elemental of all his dramatic works, the one which finally does away with language entirely, but we never see the lights go down, we never reach a terminus. What we witness here is the not-quite-completed process of exhaustion, not the final hard, cold kernel of whatever-you-wish-to-call-it (thought, language, Spinozan “substance”, etc.) which remains after all that can be has been reduced into nothing. The world of Quadrat 1+2, alien as it is, is a world that we can say obeys the laws of thermodynamics; it’s a world that could be our own. That a player still moves on the square means it’s a world with a future—only the barest traces of such, but even a bare trace is striking in comparison with the non-future, common to Beckett’s work of this period, of either oblivion or eternal return. Here is the proposal I’ve been building towards: what if this is science fiction?

This isn’t really that much of a stretch. Darko Suvin, in his foundational essay “On the Poetics of the Science Fiction Genre”, has no qualms about identifying certain works of Borges or Kafka with science fiction, so why not, then, certain works of Beckett’s? Suvin’s one-line definition of the genre, drawing on Shklovsky and Brecht, is that it is a “literature of cognitive estrangement”, which is to say a literature that takes the historical as something contingent and malleable, a launching-off point for the exploration of strange and alien possibilities, but not, as in myth or fantasy, something to be arbitrarily transformed or disregarded entirely. If one accepts this definition, which places emphasis on the nature of sci-fi’s creative operation rather than on its object-level conventions or creative lineage, Quadrat 1+2 could begin to seem like science fiction almost by default: quite simply, what else do you call a work which includes such an enormous time jump?

But let’s say, for the sake of argument, the time jump is not so enormous—after all, it’s a fact that exists, ultimately, in slightly uncomfortable parallel to the text, not really “within” it, strictly speaking; it’s something Beckett reportedly said to Dr. Müller-Freienfels, not something that’s spelled out on the page or the screen. Any interpretation hung on this hook alone is in danger of coming crashing down. But it does not hang on this hook alone. For one thing, there is the fact that, regardless of how much time separates them, Quadrat 1+2 remains, irreducibly, a work with two parts, Quad I and then, only then, Quad II. It’s not a monad, but a dyad; its logic is binary, dialogical, like a computer system. To return to the question of the “Dantean allusion”, it expresses, I think, a desire to reconcile this quality of the work with a certain understanding of Beckett which is complicated by it: firstly, by situating him within a literary and philosophical lineage, to remind the reader, perhaps slightly chidingly, that despite its extreme spareness, his mature work did not emerge into the world ex nihilo; secondly, by bringing the work into closer conformity with the model of the closed, timeless system which dominates much his other late work—because the Inferno, of course, is an eternal place, a place outside of history. But Quadrat 1+2, as we’ve established, isn’t outside of history, as comforting as that would be. It exists within the flow of time, it proposes something which is not truly fantastical, just radically estranged. This is what makes it so uniquely entrancing, and uniquely disquieting.

Beckett belongs to a lineage, true enough, but he comes at the end of it, or, at least, at an end of it. His work is a project of winding down, of reaching towards the final terminus of the thing which began to end with the development of Modernism (whenever you wish to say that was). Its vision of eternal return is one where the beginning is already the ending again. I’ve already mentioned the observed similarity the script bears to a computer script, more than a conventional dramatic one. Phyllis Carey has made the particularly interesting observation that the movements of the players across the square bear some resemblance to the movements of photons across an (analog) television screen.4 In so far as we can speak of a relationship between Quadrat 1+2 and technology, it’s clearly going against the grain to try and posit it as concerning anything prior to or somehow outside of history, as the “Dantean allusion” implies. The traces not only of modernity, but of the (at the time) cutting edge of technology are all over it. On the basis of the text, the only reasonable conclusion to draw is that its diegesis is not pre-technological, or even a-technological, but post-. I think the players are best understood as figures of some far future situation where this, these sounds, these lights, these movements on this square, are all that remains of some unfathomably advanced civilization, the only thing which it is still possible to do and the only thing which it is still necessary thing to do, for as long as possible, to stave off the inevitable moment of complete cessation, final exhaustion. Regardless of how long we wish to say “as long as possible” actually is, this is, of course, the realm of science fiction.

It’s tempting to read this purely analogically. When I rewatch the piece, I often think of a particle approaching absolute zero, not quite there yet, but cooling inexorably. You could just as easily read it as depicting the same process on the scale of the entire universe, the last few cosmic seconds before heat death. Neither of these are strictly disprovable within the interpretive framework I’ve laid out, but I think embracing them lets the interpreter off the hook, just a little bit. The fact that the players are designated in the script as “players”, rather than “figures” or “bodies” or even “actors” (when one considers that a concept or a natural force, like entropy, can “act” upon something just as much as a person can), means we should regard the beings on screen as being, in some way, the products of a situation capable of producing the concept of a “player”—that is, of a society, as social organization is the precondition which makes a distinction between “play” and “life”, or “game” and “non-game”, possible. If the players can be reduced to something less than that, like a photon, not really alive, they become quite a bit less threatening, and arguably less interesting. One no longer has to consider a life like the one Quadrat 1+2 implies. The terror of its ceaselessness, of its interminable, inexorable decline towards gray silence, is muted, softened. Of course, as I said, it’s impossible to say these aren’t just photons. But, historically, Beckett’s work has generally been about humans, or things resembling humans in most of the ways that count. If we want to be honest with ourselves, we need to be able to say that that’s us on the square, turning to the left, sidestepping the center point, the “danger zone”, the unspeakable and unknowable, the very, very last taboo, without which…? Well, we don’t want to know. Or, at least, we need to be able to say that it could be us. We need to be able to say we, too, might be convinced to cross our arms against our chest, and almost run.

The origins of Quadrat 1+2 are in an abandoned mimefrom the early 60s, the so-called J.M. Mime, intended for the Irish actor Jack MacGowran. It was, of course, never completed. That piece concerned an obsessively thorough elaboration of the possible paths, both “correct” and “incorrect”, by which two figures, identified as either a mother and son or a father and son, might move along a bisected square. The manuscript, later reproduced as an appendix in S.E. Gontarski’s book-length study of a number of Beckett manuscripts,5 resembles a mathematical text more than a dramatic one, delineating not only all the “correct” paths the family might take over the square, but eighty “possible errors”, as well. Two of its pages are almost entirely covered in dense, carefully-rendered tables of alphabetic coordinates. Further strings of such (CB, BD, DC, CA, … etc.) are contained within elegant braces. In that era, unless you happened to be a cryptographer at one of a few research institutes generously funded by a world power, this was what you had to do, more or less, to work this sort of thing out. When one thinks of the amount of human life-hours spent on this sort of rote computation throughout history, the mind begins to grow fuzzy at the sheer waste of it all. By 1980, though, things like this were on their way out. Everything had become much simpler, and much more complicated. The point J.M. Mime was making no longer needed to be made. Something purer and more distant, beyond the family unit, beyond the computational act, was required. In the waning years of the Cold War, Quadrat 1+2 proposes an alternative to nuclear apocalypse—a future in which things just continue onwards, senselessly, towards exhaustion, with nothing being revealed at all.

Herren, Graley. Samuel Beckett’s Plays on Film and Television. 2007. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Knowlson, James. Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett. 1996. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Brater, Enoch. “Toward a Poetics of Television Technology: Beckett’s Nacht und Träume and Quad.” Modern Drama, Volume 28, Number 1, Spring 1985, 48-54.

Carey, Phyllis. “The Quad Pieces: A Screen for the Unseeable.” Robin J. Davis & Lance St J. Butler (eds.), Make Sense Who May: Essays on Samuel Beckett's Later Works, 145-149. 1989. Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe.

Gontarski, S.E. The Intent of Undoing in Samuel Beckett’s Dramatic Texts. 1985. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.